THE SPREAD OF ISLAM Among the People of AFRICA AFRICA, Part ONE A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith T.W. Arnold Ma. C.I.F Professor Of Arabic, University Of London, University College. Written in 1896, revised in 1913 Rearranged by Dr. A.S. Hashim

The information we possess of the spread of Islam among the heathen population of North Africa is hardly less meager than the few facts recorded above regarding the disappearance of the Christian Church. The Berbers offered a vigorous resistance to the progress of the Arab arms, and force seems to have had more influence than persuasion in their conversion. Whenever opportunity presented itself, they rebelled against the religion as well as the rule of their conquerors, and Arab historians declare that they apostatized as many as twelve times.[2]

The army of seven thousand Berbers that sailed from Africa in 711 under the command of Ṭariq (himself a Berber) to the conquest of Spain, was composed of recent converts to Islam, and their conversion is expressly said to have been sincere: learned Arabs and theologians were appointed, "to read and explain to them the sacred words of the Quran, and instruct them in all and every one of the duties enjoined by their new religion."[5] Musặ, the great conqueror of Africa, showed his zeal for the progress of Islam by devoting the large sums of money granted him by the Khalifah Abd al-Malik to the purchase of such captives as gave promise of showing themselves worthy children of the faith :

How superficial the conversion of the Berbers was may be judged from the fact that when the pious Omar b. Abd al-Aziz in A.H. 100 (a.d. 718) appointed Ismail b. Abd Allah governor of North Africa, ten learned theologians were sent with him to instruct the Muslim Berbers in the ordinances of their faith, since up to that time they do not seem to have recognized that their new religion forbade to them indulgence in wine. The new governor is said to have shown great zeal in inviting the Berbers to accept Islam, but the statement that his efforts were crowned with such success that not a single Berber remained unconverted is certainly not correct.[7] For the conversion of the Berbers was undoubtedly the work of several centuries; even to the present day they retain many of their primitive institutions which are in opposition to Muslim law.[8] Islam took no firm root among them until it assumed the form of a national movement and became connected with the establishment of native dynasties, under which many Berbers came within the pale of Islam who before had looked upon the acceptance of this faith as a sign of loss of political independence. Of these various changes of political condition it is not the place to speak here, but in a history of Muslim propaganda the rise of the Almoravids deserves special mention as a great national movement that attracted a great many of the Berber tribes to join the Muslim community.

Abd Allah b. Yasin then recognized that the time had come for launching out upon a wider sphere of action, and he called upon his followers to show their gratitude to God for the revelation he had vouchsafed them, by communicating the knowledge of it to others:

Hereupon each man went to his own tribe and began to exhort them to repent and believe, but without success: equally unsuccessful were the efforts Abd Allah b. Yasin himself, who left his monastery in the hope of finding the Berber chiefs more willing now to listen to his preaching. At length in 1042 he put himself at the head of his followers, to whom he had given the name of al-Murabiṭin (the so-called Almoravids)—a name derived from the same root as the ribaṭ[9] or monastery on his island in the Senegal,—and attacked the neighboring tribes and forced the acceptance of Islam upon them. The success that attended his warlike expeditions appeared to the tribes of the Sahara a more persuasive argument than all his preaching, and they very soon came forward voluntarily to embrace a faith that secured such brilliant successes to the arms of its adherents. Abd Allah b. Yasin died in I059, but the movement he had initiated lived after him and many heathen tribes of Berbers came to swell the numbers of their Muslim fellow-countrymen, embracing their religion at the same time as the cause they championed, and poured out of the Sahara over North Africa and later on made themselves masters of Spain also.[10] It is not improbable that the other great national movement that originated among the Berber tribes, viz. the rise of the Almohads at the beginning of the twelfth century, may have attracted into the Muslim community some of the tribes that had up to that time still stood aloof. Their founder, Ibn Tumart, popularized the sternly Unitarian tenets of this sect by means of works in the Berber language which expounded from his own point of view the fundamental doctrines of Islam, and he made a still further concession to the nationalist spirit of the Berbers by ordering the call to prayer to be made in their own language.[11] Some of the Berber tribes, however, remained heathen up to the close of the fifteenth century,[12] but the general tendency was naturally towards an absorption of these smaller communities into the larger.

The sixteenth century witnessed the birth of a movement of active proselytizing in the Maghrib, which has been traced to the reaction excited by the successes of the Christian powers in Spain and North Africa. This gave an immense impulse to the institution of the " marabouts,"[13] and large numbers of them set out from the monastic settlements in the south of Morocco to carry a peaceful missionary campaign throughout the Maghrib, renewing the faith of the lukewarm adherents of Islam and converting their heathen neighbors.[14]

In the same century there were founded on the upper Niger two cities, destined in succeeding centuries to exercise an immense influence on the development of Islam in the Western Sudan,—Jenne,[21] founded in a.h. 435 (a.d. 1043-1044),[22] and destined to become an important trading center, and Timbuktu, the great emporium for the caravan trade with the north, founded about the year a.d, 1100. The king of Jenne, Kunburu, became a Muslim towards the end of the sixth century of the Hijrah (i. e. about a.d. 1200) and his example was followed by the inhabitants of the city; when he had made up his mind to embrace Islam, he is said to have collected together all the ulama in his kingdom, to the number of 4200—(however exaggerated this number may be, the story would seem to imply that Islam had already made considerable progress in his dominions)—and publicly in their presence declared himself a Muslim and exhorted them to pray for the prosperity of his city; he then had his palace pulled down and built a great mosque[23] in its place.[24]

According to the Kano Chronicle it was the Mandingos who brought the knowledge of Islam to the Hausa people; the date is uncertain,[30] as are most dates connected with the history of the Hausa states, because the Fulbe, who conquered them at the beginning of the nineteenth century, destroyed most of their historical records. But the importance of the adoption of Islam by the Hausas cannot be exaggerated; they are an energetic and intelligent people, and their remarkable aptitude for trade has won for them an immense influence among the various peoples with whom they have come in contact; their language has become the language of commerce for the Western Sudan, and wherever the Hausa traders go—and they are found from the coast of Guinea to Cairo—they carry the faith of Islam with them. References to their missionary activity will be found in the following pages. But of their own adoption of the faith, as well as of the rise of the seven Hausa states and their dependencies,[31] historical evidence is almost entirely wanting;[32] one of the missionaries of Islam to Kano and Katsena would certainly seem to have been a learned and pious teacher from Tlemsen, Muhammad b. Abd al-Karim b. Muhammad al-Majili, who flourished about the year 1500;[33] possibly they were affected by the great wave of Muslim influence which moved southward from Egypt in the twelfth century.[34]

Where intermarriages with such races as Arabs and Berbers have been frequent, a steady process of infiltration has gone on, and this, added to the propagandist activities of those races—Fulbe, Hausa and Mandingo—who have distinguished themselves for their zeal on behalf of their religion, would have contributed to the more rapid growth of a Muslim population, had it not been for the internecine wars that caused one Muslim state to work the destruction of another.

In the fourteenth century the Tunjar Arabs, emigrating south from Tunis, made their way through Bornu and Wadai to Darfur; others came in later from the east;[37] one of their number named Aḥmad met with a kind reception from the heathen king of Darfur, who took a fancy to him, made him director of his household and consulted him on all occasions. His experience of more civilized methods of government enabled him to introduce a number of reforms both into the economy of the kings household and the government of the state. By judicious management, he is said to have brought the unruly chieftains into subjection, and by portioning out the land among the poorer inhabitants to have put an end to the constant internal raids, thereby introducing a feeling of security and contentment before unknown. The king having no male heir gave Aḥmad his daughter in marriage and appointed him his successor,— a choice that was ratified by the acclamation of the people, and the Muslim dynasty thus instituted has continued down to the present century. The civilising influences exercised by this chief and his descendants were doubtless accompanied by some work of proselytism, but these Arab immigrants seem to have done very little for the spread of their religion among their heathen neighbors. Darfur only definitely became Muslim through the efforts of one of its kings named Sulayman who began to reign in 1596,[38] and it was not until the sixteenth century that Islam gained a footing in the other kingdoms lying between Kordofan and Lake Chad, such as Wadai and Baghirmi. The first Muslim king of Baghirmi was Sultan Abd Allah, who reigned from 1568 to 1608, but the chief center of Muslim influence at this time was the kingdom of Wadai, which was founded by Abd al-Karim about A.D. 1612, and it was not until the latter part of the eighteenth century that the mass of the people of Baghirmi were converted to Islam.[39]

But the history of the Muslim propaganda in Africa during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is very slight and wholly insignificant when compared with the remarkable revival of missionary activity during the present century. Some powerful influence was needed to arouse the dormant energies of the African Muslims, whose condition during the eighteenth century seems to have been almost one of religious indifference. Their spiritual awakening owed itself to the influence of the Wahhabi reformation at the close of the eighteenth century; whence it comes that in modern times we meet with some accounts of proselytizing movements among the Negroes that are not quite so forbiddingly meager as those just recounted, but present us with ample details of the rise and progress of several important missionary enterprises. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, a remarkable man, Sheikh Uthman Danfodio,[40] arose from among the Fulbe[41] as a religious reformer and warrior-missionary. From the Sudan he made the pilgrimage to Mecca, whence he returned full of zeal and enthusiasm for the reformation and propagation of Islam. Influenced by the doctrines of the Wahhabis, who were growing powerful at the time of his visit to Mecca, he denounced the practice of prayers for the dead and the honor paid to departed saints, and deprecated the excessive veneration of Muhammad himself; at the same time he attacked the two prevailing sins of the Sudan, drunkenness and immorality. Up to that time the Fulbe had consisted of a number of small scattered clans living a pastoral life; they had early embraced Islam, and hitherto had contented themselves with forming colonies of shepherds and planters in different parts of the Sudan. The accounts we have of them in the early part of the eighteenth century, represent them to be a peaceful and industrious people; one[42] who visited their settlements on the Gambia in 1731 speaks of them thus: "In every kingdom and country on each side of the river are people of a tawny color, called Pholeys (i.e. Fulbe), who resemble the Arabs, whose language most of them speak; for it is taught in their schools, and the Quran , which is also their law, is in that language. They are more generally learned in the Arabic, than the people of Europe are in Latin; for they can most of them speak it; though they have a vulgar tongue called Pholey. They live in hordes or clans, build towns, and are not subject to any of the kings of the country, tho they live in their territories; for if they are used ill in one nation they break up their towns and remove to another. They have chiefs of their own, who rule with such moderation, that every act of government seems rather an act of the people than of one man. This form of government is easily administered, because the people are of a good and quiet disposition, and so well instructed in what is just and right, that a man who does ill is the abomination of all......." Danfodio united into one powerful organization these separate communities, scattered throughout the various Hausa states. The first outbreak occurred in the year 1802, in the still pagan kingdom of Gober, which had gained ascendancy over the northernmost of the Hausa states; the attempt of the king of Gober to check the growing power of the Fulbe in his dominions caused Danfodio to raise the standard of revolt; he soon found himself at the head of a powerful army, which attacked not only the pagan tribes, forcing upon them the faith of the Prophet, but also the Muslim Hausa states. These fell one after another and the whole of Hausaland came under the rule of Danfodio before his death in 1816. His grave in Sokoto is still an object of reverence to large numbers of pilgrims.

The introduction of law and order into Southern Nigeria has favored the propaganda of Islam as in other parts of Africa that have come under European rule. The Hausa Muslims, some of whom belong to the Tijaniyyah order, have been able to move freely about the country and to penetrate among pagan tribes which had hitherto kept all Muslim influences rigidly at bay. In the Yoruba country particularly Islam is said to be rapidly gaining ground. There is a legend of an unsuccessful attempt made by a Muslim missionary as early as the eleventh or twelfth century; he was a Hausa who came to Ife, the religious capital of the pagan Yoruba country, and used to call the people together and read them passages from the Quran; he could only speak the Yoruba language imperfectly, and with a foreign accent he would repeat to his listeners, " Let us worship Allah : He created the mountain, He created the lowland, He created everything, He created us." He did this from time to time without succeeding in winning a single convert, and died a few months after his arrival in Ife. After his death his Quran was found hanging on a peg in the wall of his room, and it came to be worshipped as a fetish.[43] Where this early apostle of the faith failed, his modern co-religionists have achieved a remarkable success. During the period of anarchy before the British occupation, the Muslims were for the most part congregated in large, walled towns, but under the new conditions of security they are able to reside permanently in villages, and near the scenes of their agricultural labors, and Muslim influences have thus become more widely extended over the country. As in German East Africa, the presence of Muslims among the native troops has been found to be favorable to the extension of their faith, and the pagan recruits often adopt Islam in order to escape ridicule and gain in self-respect.[44] In the Ijebu country also, in Southern Nigeria, a quite recent propagandist movement has been observed; Islam was only introduced into this part of the country in 1893, and in 1908 there was one town with twenty, and another with twelve mosques.[45] This rapid spread of the Muslim faith is particularly noticeable along the banks of the river Niger in Southern Nigeria; a Christian missionary reports: "When I came out in 1898 there were few Muslims to be seen below Iddah.[46] Now they are everywhere, excepting below Abo, and at the present rate of progress there will scarcely be a heathen village on the river-banks by 1910."[47] There has thus been much missionary work done for Islam in this part of Africa by men who have never taken up the sword to further their end,—the conversion of the heathen. Such have been the members of some of the great Muslim religious orders, which form such a prominent feature of the religious life of Northern Africa. Their efforts have achieved great results during the nineteenth century, and though doubtless much of their work has never been recorded, still we have accounts of some of the movements initiated by them. Of these one of the earliest owed its inception to Si Aḥmad b. Idris,[48] who enjoyed a wide reputation as a religious teacher in Mecca from 1797 to 1833, and was the spiritual chief of the Khaḍriyyah; before his death in 1835 he sent one of his disciples, by name Muhammad Uthman al-Amiir Ghani, on a proselytizing expedition into Africa. Crossing the Red Sea to Kossayr, he made his way inland to the Nile; here, among a Muslim population, his efforts were mainly confined to enrolling members of the order to which he belonged, but in his journey up the river he did not meet with much success until he reached Aṣwan; from this point up to Dongola, his journey became quite a triumphant progress; the Nubians hastened to join his order, and the royal pomp with which he was surrounded produced an impressive effect on this people, and at the same time the fame of his miracles attracted to him large numbers of followers. At Dongola Muhammad Uthman left the valley of the Nile to go to Kordofan, where he made a long stay, and it was here that his missionary work among unbelievers began. Many tribes in this country and about Sennaar were still pagan, and among these the preaching of Muhammad Uthman achieved a very remarkable success, and he sought to make his influence permanent by contracting several marriages, the issue of which, after his death in 1853, carried on the work of the order he founded—called after his name the Amirghaniyyah.[49] A few years before this missionary tour of Muhammad Uthman, the troops of Muhammad Ali, the founder of the present dynasty of Egypt, had begun to extend their conquests into the Eastern Sudan, and the emissaries of the various religious orders in Egypt were encouraged by the Egyptian government, in the hope that their labors would assist in the pacification of the country, to carry on a propaganda in this newly-acquired territory, where they labored with so much success, that the recent insurrection in the Sudan under the Mahdi has been attributed to the religious fervor their preaching excited.[50]

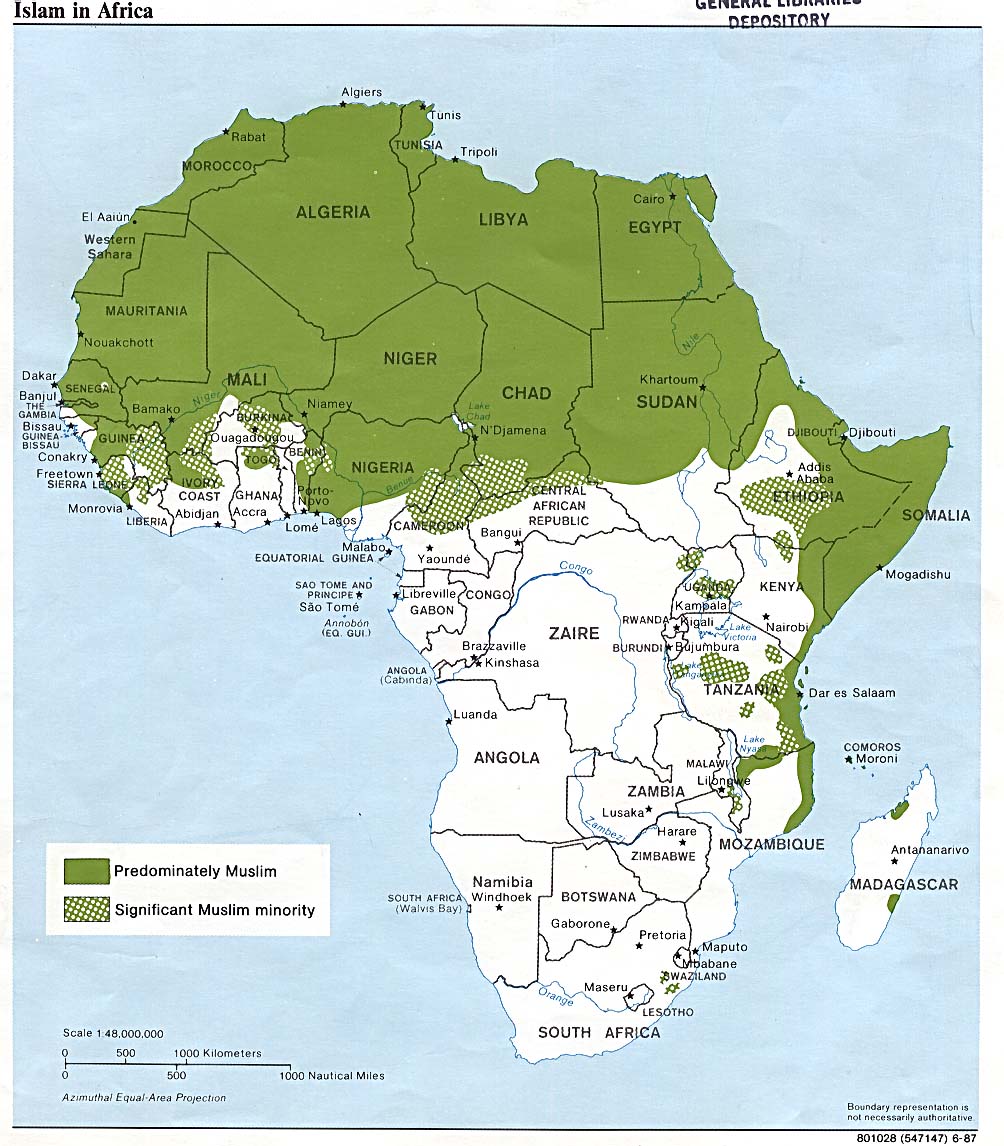

[1] An excellent map of the extent of Islam in Africa is to be found in The International Review of Missions," vol. i. p. 652. [2] Fournel, vol. i. p. 271. [3] i.e. the diviner or priestess; her real name is unknown. [4] Fournel, vol. i. p. 224 [5] Makkarī, vol. i. p. 253. [6] Makkarī. vol. i. p. Ixv. [7] Fournel, vol i. p. 270. [8] For these and the heretical movements that reveal survivals of the earlier Berber faith, see Goldziher. Materialen znr Kenntniss der Almohadenbewegung in Nordafrika (Z D M G, vol. xli, p. 37 sqq.). [9]On this word, see Doutté, Notes sur 1’lslam maghribin. (Revue de l'histoire des religions, tom. xli. p. 24-6.) [10] Ibn abī Zar, pp. 168-73. A. Muller, vol. ii. pp. 611-13. [11] Ibn abī Zar', p. 250. Goldziher, op. laud., p. 71. [12] Leo Africanus. (Ramusio, tom. i. p. II) [13]. مرابط [14] Doutté, xl. p. 354; xli. pp. 26-7. [15] Depont et Coppolani, p. 127 sq. [16] It is not the place here to deal with the rise and political history of the various kingdoms of the Western Sudan; this has been done most fully for the English reader by Lady Lugard in her work entitled, " A Tropical Dependency. An Outline of the Ancient History of the Western Sudan, with an Account of the Modern Settlement of Northern Nigeria." (London, 1905.) See also H. F. Helmolt: The World's History, vol. iii. chap. ix. (London, 1903.) [17] Blau, p. 322. [18] Leo Africanus. (Ramusio, tom. i. pp. 7, 77.) [19] Meyer, p. 91. [20] Ta'rīkh al-Sūdān, p. 3. [21] Jinni or Dienné. [22] So Meyer following Barth; the Ta'rīkh al- Sūdān (p. 12) places the date about three centuries earlier. [23] Felix Dubois gives a plan and reconstruction of this mosque, which was destroyed by order of Shaykhu Aḥmadu about 1830, in " Tombouctou la Mystérieuse," chap.ix. [24] Ta'rikh al-Sūdān, pp. 12-13. [25] Ta'rīkh al- Sūdān, p. 21. [26] Ibn Baṭūṭah, tome iv. pp. 421-2. [27] Ramusio, tom. i. p. 78. [28] Winwood Reade describes them as " a tall, handsome, light-color ed race, Muslim s in religion, possessing horses and large herds of cattle, but also cultivating cotton, ground-nuts, and various kinds of corn. I was much pleased with their kind and hospitable manners, the grave and decorous aspect of their women, the cleanliness and silence of their villages." (W. Winwood Reade: African Sketchbook, vol. i. p. 303.) [29] Waitz, IIer Theil, pp. 18-19. [30] Palmer (p. 59) places its introduction into Kano between A.D. 1349 and 1385, another Hausa chronicle makes the reign of the first Muhammadan king of Zozo begin about 1456. (Journal of the African Society, vol. ix. p. 161.) [31] For the various enumerations of these, see Meyer, p. 27. [32] As in other parts of the Muslim world, tradition places the first introduction of Islam in the lifetime of the founder and gives the name of al-Fazāī, a reputed companion of the Prophet, as the apostle of the Hausa people. (J. Lippert: Sudanica. MSOS, iii. parts, P. 204. (Berlin, 1900.) [33] Mischlich and Lippert, pp. 138-9. [34] Meyer, loc. cit. Artin Pasha (p. 62) puts the beginning of this infiltration of Muslim Arabs as early as the eighth century. [35]Becker, Geschichte des ostlichen Sudan, p. 162-3. Blau, p. 322 Oppel. p. 289. At the close of the fourteenth century 'Umar b. Idris moved his capital to the west of Lake Chad in the territory of Bornu, by which name the kingdom of Kanem became henceforth known. [36] Maurice Delafosse, p. 87. [37] Becker: Geschichte des ōstlichen Sūdān, pp. 161-2. [38] R. C. Slatin Pasha: Fire and Sword in the Sudan, pp. 38, 40-2. (London, 1896) [39] Westermann, p. 628. [40] Oppel, p. 292. Meyer, pp. 36-7. Westermann, pp. 629-30. [41] Fulbe (sing. Pul) is the name by which these people call themselves; upwards of a hundred variants are applied to them by their neighbours, the commonest of which are Fulah and Fulani. (Meyer, p. 28.) [42] Francis Moore, pp. 75-7. [43] R. E. Dennett: Nigerian Studies, pp. 12, 75. (London, 1910.) [44] Islam and Missions, pp. 71-3. The Muslim World, pp. 296-7, 351 [45] Church Missionary Review (1908), p. 640. [46] A town on the Niger, just south of the northern boundary of Southern Nigeria. [47] Church Missionary Society Intelligencer (1902), p. 353. [48] Rinn, pp. 403-4. [49] Le Chatelier (I), pp. 231-3 [50] Le Chatelier (2), pp. 89-91.

|