Al-Jawaad's Lifetime

|

EVENTS AND

HAPPENINGS: |

|

Ø

Birth of Muhammad Al‑Jawaad |

|

Ø

Al‑Jawaad's father (Al‑Ridha)

takes special care of him |

|

Ø

Imam Al‑Ridha tutors his son

Al‑Jawaad early |

|

Ø

Al‑Jawaad is well versed in the

Quran and Hadith at an early age |

|

Ø

The family moves to Khurasan |

|

Ø

Imam Al‑Ridha dies when Al‑Jawaad

was a young lad |

|

Ø

After a short stay in Medina,

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon requests

Al-Jawaad to attend Baghdad |

|

Ø

In the contest Al-Jawaad argues

with and defeats the highest

Jurist, Ibn Al-Ak'tham |

|

Ø

Al-Jawaad marries Umm Al‑Fadhl,

the daughter of Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon |

|

Ø

Al-Jawaad moves back to Medina

and stays for 7 years |

|

Ø

Is called upon by Khalifa Al‑Mu'tasim

to be in Baghdad |

|

Ø

Maaliki, Hanafi, and Shafi'i

movements are active |

|

Ø

Al‑Jawaad dies in his twenties |

|

Ø

Al‑Haadi [Al-Naqi] is the Imam. |

BIRTH

Year 195H:

Al‑Jawaad was born in Medina in

the year 195H. It had been a

long wait for him since his

father Imam Al‑Ridha was married

for a good many years but without

an offspring. At the time of

Al‑Jawaad's birth his father was

about 45 yrs old. Al‑Ridha said

the Athan in the baby's right ear

and the Iqaama in the left, and

performed the Aqeeqah as was done

to every newborn in the family,

in compliance with the Prophet's

(pbuh) recommendation. Al‑Ridha

became greatly attached to his

young son who showed signs of

exceptional intelligence.

Al‑Jawaad grew up in a pious

environment revered for its

spirituality, virtue and

righteousness, and he was cared

for with love and tender care.

Al‑Jawaad's

lineage came from the line of

Ahlul Bayt on the one hand and

from a righteous mother on the

other hand. His mother's name

was Subeyka who was from the

Nubah (Africa, Sudan area

nowadays). Subeyka was of the

progeny of

Mary (Maria Al‑Qubtiyyah)

who was the wife of Prophet

Muhammad (pbuh) and the mother of

Ibrahim, the Prophet's son who

died in childhood.

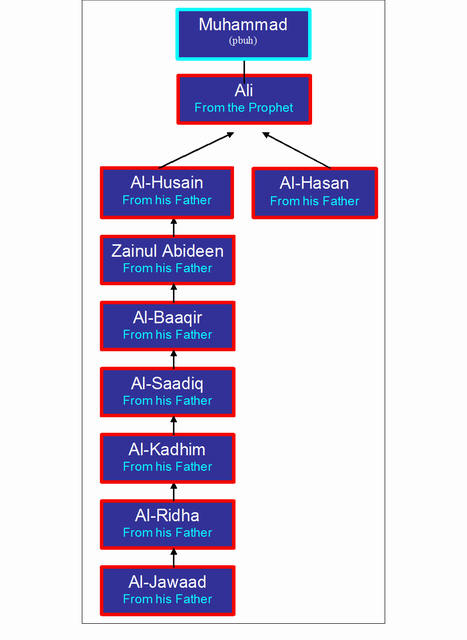

Lineage

|

Al-Jawaad |

|

Parents |

Al-Ridha |

Subeyka, Umm Wilid,

Progeny of Mary Qubtiyyah |

| |

|

Grandfather |

Al-Kadhim |

|

AS AL‑JAWAAD GROWS

UP

From the

beginning Al‑Jawaad grew attached

to his father Imam Al‑Ridha, it

was mutual love and

understanding. Al‑Jawaad

frequently enjoyed going with his

father to various places

especially to the Prophet's

Mosque where he frequently

noticed his father praying,

saying Du'aa, and crying. This

left a lasting impression on

him. Al‑Jawaad was the ever

questioner, investigator, and

researcher, and his questions

increased in their complexity.

Of the many

narrations of Traditionists who

asked Imam Al‑Ridha about the

subsequent Imam after him, one

narration stands out. When

asked, Imam Al‑Ridha pointed to

the young Al‑Jawaad then answered

that Al‑Jawaad would be the

subsequent Imam as he grew.

Al-Ridha was

quoting Muhammad (pbuh) by saying

to his uncle, “The son of the

best Nubian maid-servants

[Al-Jawaad] will be among his

[Al-Ridha's] descendants. He

will be pursued, exiled, and

deprived of his father. His

grandson [Al-Mahdi] will be the

Imam who goes into occultation.

It will be said that he

[Al-Mahdi] has died or had been

killed or any such excuse.”

(Al-Irshad,

Al-Mufeed, page 481.)

Year 202H: At the Age

of 7 years:

Like his

forefathers, Al‑Jawaad displayed

a remarkable capacity to learn

and a very sharp memory. By the

age of 7 years Al‑Jawaad had

already memorized the Holy Quran

and at this young age he learned

the meaning of its various parts,

the historical background of some

Ayahs, and many of their

intricacies. He had an excellent

teacher in his father.

Al‑Jawaad

loved the explanations his father

(Imam Al‑Ridha) gave. Al‑Jawaad

asked increasingly complex

questions for his age and he

received appropriate answers by

his father.

“Father!”

Al‑Jawaad asked as the two were

alone, “Why did the civil war

take place? Aren't Khalifas

Al‑Amin and Al‑Ma'Moon brothers?”

(These

conversations are theoretical,

but with the intention of

bringing out the issues of the

time that affected the Muslim

Ummah. These conversations are

not to be taken as if they had

literally taken place.)

Used to such questions from

Al-Jawaad and finding it the

proper occasion, Imam Al‑Ridha

answered warmly, “Son, the father

of these two was Khalifa Haroon

Al‑Rashid as you know, the

unquestioned Khalifa with the

very large ego. On a personal

whim Al‑Rashid made a very unwise

decision to divide the domain of

the Muslim Ummah [State] between

his two sons. His decision in

effect divided the whole Muslim

State unnecessarily. Khalifa

Al‑Amin foolishly aimed at

removing his brother Al‑Ma'Moon

from his position despite the

solemn agreement acknowledged by

the two and their father. This

of course led to a horrible war

about the throne; as usually

happens in quest and for the love

of power. The outcome of that

war was an extensive destruction

of many parts of Baghdad, killing

of people and devastating

families, and finally the

beheading of Al‑Amin who had

started the war. It was

gruesome, very gruesome. In the

meantime, a) Baghdad stopped

being the capital and seat of

power for many years, b) the

Khilaafah changed hands, and c)

the armed forces and the

administration went to strange

hands.”

“I am afraid

of one thing though,” Imam

Al‑Ridha said after a short

pause.

“What is

that?” Al‑Jawaad asked

inquisitively. Imam Al‑Ridha

answered, “Son, in the last few

months Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon has

been requesting that I go to his

headquarters in Maru in Khurasan,

more than 2,000 miles from here,

to take the Khilaafah. This is

something I abhor, I'd rather

stay here and continue to teach

anytime than be there. I do not

like the play of politics, nor be

a part of that system. To

support his Khilaafah, I think

Al‑Ma'Moon is cleverly using our

position and taking advantage of

the love people have for us,

Ahlul Bayt.” Al‑Ridha paused for

a few seconds then continued,

“Son, you are going to be the

Imam after me. Your

comprehension is very high and it

is superior to that of most

people many folds your age. You

and I have looked into the Jafr

and the books of Knowledge Imam

Ali had left. I should also tell

you that when you become the Imam

you will also be directed by two

ways as all the Imams including

myself have:

►

The first way is by an Unerring

Inspiration.

►

The second is by way of the Al-Muhad'dith.”

(As

narrated by Abdullah Ibn Tawoos.

See Seerah of the Twelve Imams,

H.M. Al-Hassani, Vol. 2, Page

414.)

Surprised,

Al‑Jawaad immediately asked,

“What do you mean father?”

The two were

still sitting in the room, the

sun was shining with its warm

rays and the breeze was cool.

Al‑Jawaad was very curious.

With

understanding and a smile on his

face Imam Al‑Ridha replied, “Son,

our answers to people's inquiries

or questions are not always from

our studies of the Corpus of

Knowledge. Our answers also come

by way of inner inspiration, as

if there is a compeller within us

giving the answer. The Imam's

inspiration is accurate and

unerring, it is correct.

As to Al-Muhad'dith, we may hear

his answer but see no one. When

we reiterate what we had heard

the answer is amazingly clear, to

the point and correct.” (Al-Saadiq

was quoted saying “We have Al-Naq'ru

fi Al-Asmaa' and Al-Naqt fi Al-Quloob”,

meaning the Muhad'dith and the

Un-Erring Inspiration

respectively. (See Al-Irshad,

Al-Mufeed Page 414.)

Excitedly Al‑Jawaad said, "This

is very exciting father, and I

certainly will do my duty as an

Imam the best I can.”

|

The Corpus of Knowledge

|

-

The Holy Quran in

chronological order of Ayah

Revelations

-

Tafseer of the Holy Quran

consisting of three large

volumes, called Mus'haf

Fatima. Written in her honor.

-

The books of Hadith, as Imam

Ali had recorded them, called

Saheefa of Ali.

-

The books about Al‑Ah'kaam,

detailing the rules and

regulations of the Shari'ah.

(Halal and Haram, Ethics,

Mu'aamalaat, among other

important Islamic subjects.)

-

The books about the Jafr: A)

The White Jafr (About

knowledge of the Prophets,

life happenings, and other

Mystic matters. B) The Red

Jafr, comprising rules and

matters about and involving

wars.

|

“Son!”

Al‑Ridha asserted again, “Even

though you are very young, your

mind is better than the minds of

most people several times your

age. I am in my early fifties

and my final days may be soon

approaching, and if so your duty

as an Imam will be even more

difficult on account of your

age. You will have to prove your

mettle. This is the reason I

have been concentrating so

insistently on your education.

Remember, Allah will support you

with the Divine Light. It looks

that soon I am going to be forced

to go to Khurasan, hopefully with

the family so that we continue to

be together.” After a pause Imam

Al‑Ridha continued, “Yes son, you

will be the Imam after me, and

you have to carry on no matter

what the circumstances are, but

with prudence and care. Teaching

the correct Message of Islam is

what counts, and through your

grandson the awaited Al‑Mahdi

will be born. This line of

heritage is most sacred, you have

to keep that in mind,” answered

Al‑Ridha affirmatively.

Al‑Jawaad

responded, “Many thanks father

and I am grateful to Allah for

the knowledge you are giving me.”

Year 204H:

At the Age of 10 years:

By the age of

about 10 years, Al‑Jawaad had

been in Khurasan for about 3

years in company of his father

Imam Al‑Ridha. He had learned

further at the hands of his

father and had witnessed the

numerous debates in the court of

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon whereby his

father was the source for

information and the ultimate

reference to invited scholars as

numerous as they were. Al‑Jawaad

had learned of the courtly life

in the Royal Palace and the large

number of personalities that get

involved in it.

Lately

however, Al-Jawaad had heard of

the advice his father Imam

Al‑Ridha had given to Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

which pointed to him to:

-

leave Maru and

make Baghdad his capital

again,

-

remove his

Prime Minister from office

(since that person had

deceived him), and

-

remove him

[Al-Ridha] from the

heir‑apparent position.

According to

this suggestion there came about

busy preparations for the purpose

of moving the headquarters of the

government and the personnel from

Maru to Baghdad.

On their way

to Baghdad Al‑Jawaad became

extremely distressed since his

father fell ill, and he was most

grieved when 3 days later Imam

Al‑Ridha died. It was a very

painful experience and he was in

mourning for sometime. After

this Al‑Jawaad and the family

left for Medina, while Khalifa

Al‑Ma'Moon continued on his way

to Baghdad. (Many

historians, including Al-Mufeed

claim that Al-Jawaad was left

behind in Medina when Al-Ridha

was requested to leave for

Khurasan. However, H.M. Al-Hassani

(in his book of Seerah of the

Twelve Imams, Vol. 2, Page 430)

claims it was more likely that

Al-Jawaad had accompanied his

father to Khurasan.)

Al-Jawaad stayed in Medina for

some time carrying out his duties

as the Imam, but sometime later

Khalifa Al-Ma'Moon sent a special

request, asking him to move to

Baghdad. Accordingly Imam

Al-Jawaad moved to Baghdad and

stayed there for 8 years, then

returned to Medina in compliance

to his wishes.

FROM BAGHDAD BACK

TO MEDINA:

AL‑JAWAAD GOES

BACK IN MEMORY

Imam

Al‑Jawaad was traveling leaving

Baghdad to go to Medina, for he

had disliked his stay in Baghdad

and requested his father‑in‑law

(Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon) to give him

permission to leave Baghdad.

Al‑Jawaad was accompanied by his

wife

Umm Al‑Fadhl, the

daughter of Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon,

along with many companions of

travel and attendants. Al‑Jawaad

was approaching his twenties, he

was very anxious to go back to

his beloved Medina after being

away for 8 long years in Baghdad.

(According

to some sources such as Murooj

Al-Dhahab, Al-Mas'oodi, Al-Jawaad

left sometime before 218H. in

which year Al-Ma'Moon died.

Other sources claim it was in the

year 212H.)

During his

travel Imam Al-Jawaad reviewed

various periods in his life

considering many happenings too.

He considered the following:

►

his early Imamah,

►

the request by

Khalifa Al-Ma'Moon,

►

the contest with

Ibn Al-Ak'tham,

►

the marriage to

Umm Al-Fadhl,

►

his works in the

Khalifa Court

►

his works in

Baghdad as an Imam, and

►

his reflection

about his devotees.

Year 204H:

Al-Jawaad's early Imamah:

Al‑Jawaad

went back in memory to the time

his father Imam Al‑Ridha had died

and the family left Khurasan.

Al‑Jawaad vividly remembered his

experience when they arrived in

Medina and how at a tender age he

had to answer the numerous Fiqh

questions presented to him by

people, not only to test the

depth of his knowledge to assert

his Imamah but also to learn from

him. He remembered how leading

personalities from various

provinces gathered at Haj time to

test his knowledge, then left

satisfied. Al‑Jawaad knew, as

his father had told him before,

that he had to prove his mettle

due to his young age.

Year 205H: The request

of Khalifa Al-Ma'Moon:

Memory now

took Al‑Jawaad to the time

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon had sent for

him to leave Medina and move to

Baghdad. Al‑Jawaad remembered

how he did not cherish leaving

Medina, but the Khalifa insisted

on his request.

Upon

arriving in Baghdad, Al‑Jawaad

remembered, Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

received him with great honor and

introduced him to the high

officials, the elders of Benu

Abbas, the high judges, and the

military personnel. The Royal

Palace and headquarters of the

Khalifa were magnificent beyond

compare, the courtiers,

attendants, dignitaries, each had

his special place according to

his importance. Baghdad, Imam

Al‑Jawaad thought, was a

metropolitan town of glitter and

much wealth. But when he arrived

Baghdad was still scarred and

damaged due to the civil war

(which had ended many years

earlier), but they were still

rebuilding.

Year 205H:

Al-Jawaad's contest with Ibn Al-Ak'tham:

The thoughts

took Imam Al‑Jawaad back to the

early days of his arrival at

Baghdad, when not long afterwards

he heard murmurs of how Benu

Abbas, their young or old, had

resented Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon's

gesture toward him. Imam

Al‑Jawaad knew the formidable

task ahead of him, and how

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon had challenged

anyone in a context to outsmart

Al‑Jawaad in any field of Islamic

Tradition of any form. Imam

Al‑Jawaad recalled how Benu Abbas

took on the challenge and

appointed for the debate the

greatest Supreme Justice of the

time, Ibn Al‑Ak'tham. Ibn Al‑Ak'tham

was known to be superb in the art

of argument and persuasion, and a

highly respected person in

Baghdad. Ibn Al‑Ak'tham came

fully prepared and Al‑Jawaad was

ready for him. Imam Al‑Jawaad

knew that Benu Abbas' move, if

successful, was an attempt to

discredit him [Al-Jawaad] and

perhaps stop Al‑Ma'Moon from

giving his daughter in marriage

to him.

Al‑Jawaad

entered the assembly hall for the

debate, looked at the huge

assembly of Baghdad's prominent

men and eminent personnel and

numerous elders of Benu Abbas.

They were all seated in the

magnificent assembly hall with

expectant looks on their faces.

Al‑Jawaad, although only in his

early teens, knew he had faced

similar challenges in Medina

before, but now he was to be

tested in Baghdad. Al‑Jawaad

never forgot the curious but

anxious looks on the faces of the

audience when Ibn Al‑Ak'tham took

his place and the debate started.

Proud of

himself, Ibn Al‑Ak'tham cleared

his throat then presented the

most complex Fiqh intricacy he

could think of, then waited for

the reply.

To answer

him the teenage Al‑Jawaad

requested Ibn Al‑Ak'tham to

clarify his question and to

indicate which of the 11

subdivisions of that question he

meant.

Ibn Al‑Ak'tham

was stunned and he could not

answer back for he did not know

anything about any subdivisions.

The lines on his face became

contorted, he became pale with

embarrassment, he knew he was in

a predicament. Ibn Al-Ak'tham

stuttered and had to nervously

acknowledge that he knew nothing

about any subdivisions. Ibn Al-Ak'tham

knew his reputation was at stake.

Silence fell

on the whole audience, all 900

scholars, not including the

nobility and dignitaries —they

were dumbfounded but extremely

impressed. They were delighted,

excited and enthused at the same

time. “How remarkable!” they

thought. (Ibn

Al-Ak'tham asked Al-Jawaad, “What

is the atonement for a person who

hunts a game while he is dressed

in pilgrimage garb?”

Al-Jawaad

asked back, “Your question lacks

definition. You should first

clarify whether the game was

outside the sanctified area or

inside it; whether the hunter was

aware of his sin or did he do it

in ignorance; did he kill the

game purposely or by mistake; was

the hunter a slave or a free man;

was he an adult or a minor; did

he commit the sin for the first

time or had done it before; was

the hunted game a bird or

something else; was it a small or

a big one; was the sinner sorry

for the misdeed or did he insist

on it; did he kill it secretly at

night or openly during daylight;

did he put on the pilgrimage garb

for Haj or for the Omrah? Once

these questions are answered I'll

be glad to answer your

questions.”

As Ibn Al-Ak'tham

was bewildered and speechless, he

began to stutter so that people

in the assembly were aware of his

predicament.

Al-Ma'Moon

then asked Al-Jawaad to give his

answers to each condition he had

raised. Al-Jawaad did so, and

the excitement of the gathering

was great.

(See Al-Irshad,

Al-Mufeed, Page 486.)

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

broke the silence and said,

“Did I not tell you that this

Progeny (of Ahlul Bayt) has been

gifted by the Almighty with

limitless knowledge? Don't you

see that no one can cope even

with the young of this noble

house?” (Al-Irshad,

Al-Mufeed, page 489.)

meaning, “Didn't I tell you that

he was the most enlightened, the

most knowledgeable, and the most

insightful of all?”

Benu Abbas

were soundly defeated, they knew

it, they had disgusted looks on

their faces; they admitted

defeat—conceding sheepishly.

Shortly

after that, Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

requested Imam Al‑Jawaad to give

the answer to the complex Fiqh

query and its subdivisions as

presented by Ibn Al‑Ak'tham.

Al‑Jawaad explained it in detail,

of course including the answers

to each of the 11 subdivisions,

and to the satisfaction of all.

The intensely curious audience by

now looked up to Al-Jawaad with

awe and a great sense of

admiration.

“Yes it was

something,” Al‑Jawaad thought to

himself reflecting, as he

continued in his travel.

The thoughts

took Al‑Jawaad further, to the

period of his 8 year stay in

Baghdad and how he had not wanted

to live in the magnificent Royal

Palace of the Khalifa. Instead,

he wanted to identify with the

people, to be one of them, thus

he insisted on living in a rented

house not too far from the seat

of the government, but lacking

all the opulence and riches of

the Royal Palace. He did this

despite the insistent objections

of his wife Umm Al‑Fadhl, a girl

raised in the luxury of the

Palace and used to the services

of the hundreds of slaves at her

disposal.

Al-Jawaad's

marriage to Umm Al-Fadhl:

Imam

Al‑Jawaad's thoughts took him to

his marriage to Umm Al‑Fadhl, the

daughter of Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon.

It was soon after that fateful

debate that Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

gave his daughter (Umm Al‑Fadhl)

in marriage to Al‑Jawaad. Imam

Al‑Jawaad knew that the marriage

was perhaps a move partly

political, in an attempt to

perhaps pay back what was due

Ahlul Bayt. However, more

importantly it was because

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon aimed to

appease the Imamah‑Asserters by

such a bond; thus facing fewer

uprisings against him. “Or

perhaps, Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon,”

Al‑Jawaad thought, “wanted to

move him [Al-Jawaad] away from

the center of his activity in

Medina, a move to weaken or stunt

the works of Ahlul Bayt in

Medina.”

Whatever

reason Al-Ma'Moon had, Al‑Jawaad

thought, his marriage to Umm Al‑Fadhl

was not a smooth one. Al‑Jawaad,

who had an extremely keen mind

and a penetrating insight, knew

that Umm Al‑Fadhl was childish,

egotistical, self‑centered, and a

spoiled woman of luxury.

Al‑Jawaad knew that his wife

could not understand the lofty

position he held, i.e., being the

Imam of the Ummah and the supreme

`Marji'

(Reference) at the time. Anyway,

Al‑Jawaad thought, that was fate,

and he graciously accepted it.

Al-Jawaad's works in the

Khalifa's Court:

The thoughts

took Imam Al‑Jawaad further, for

the travel was a way not only to

be alone for himself but also for

reflecting. He thought of the

numerous times he sat on the

right side of the Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

to give verdicts and judgments to

an ever large number of people,

just as his father had done in

Khurasan a decade before. Imam

Al‑Jawaad was aware of the great

sentiment of the people for him,

they endearingly call him Ibn

Al‑Ridha. The esteem and

admiration people of Baghdad had

for him was such that wherever he

went crowds of people came to see

him or ask him questions.

At the same

time however other people feared

and resented him, mainly Benu

Abbas. Al‑Jawaad knew that Benu

Abbas were unduly worried about

losing their status, positions of

power and privileges, for it

afforded high living, luxury,

self‑indulgence, and high

comfort. They were the people

who held the power of the

Khilaafah and used it to their

advantage and did not want to let

it go.

Al-Jawaad's works in Baghdad as

an Imam:

Imam Al‑Jawaad

was fully aware too, that the

livelihood of many scholars of

Islamic sciences and most

Justices (Qadhi) depended on the

government. These people

resented his overwhelming

presence among them, not only

because Imam Al-Jawaad was young

in an age that glorified the

elders, but also because his

verdicts, mode of reasoning, and

conclusions were at such a high

level that none could ever match

them. Anyway, Al‑Jawaad thought,

the directives, the advice, the

verdicts, and the counsel he gave

in Baghdad had their positive

impact.

Imam

Al‑Jawaad thought Baghdad was an

interesting town, and the opulent

court of his father‑in‑law

(Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon) was even

more fascinating, if not

arresting. But, Al‑Jawaad

thought, he was glad he was

leaving that atmosphere and going

to Medina, to be in the Masjid

Al‑Nabawi near the tomb of the

Prophet (pbuh). How good it

would be to be again with the

family, relatives, friends, and

students alike. This time,

however, for good or bad, his

wife Umm Al‑Fadhl was with him.

Al-Jawaad reflects about the

Golden Chain of Narration:

Imam Al‑Jawaad

reflected back even further,

about his early childhood and the

enormous material he had learned

from his father Al‑Ridha.

Al‑Jawaad knew how very keen he

was about the voluminous books

which were left by Imam Ali, and

their immense value. He also

knew that his forefathers were

the Ultimate Knowledge Reference

of the Islamic world, Al‑Marji',

each during his Imamah.

|

The Golden Chain of

Narration |

Imam

Al‑Jawaad often remembered how

his forefathers repeatedly said

that their narration was the same

as that of their fathers up to

Prophet Muhammad (pbuh).

Al-Jawaad knew he was a link in

the continuation of the works for

Islam as Muhammad (pbuh) had

taught it. He knew people

appreciated his excellent

character, being the example to

others in every respect,

enjoining the good and

prohibiting the corrupt and

evil. Al‑Jawaad's mission was

the same as his forefathers',

explaining the Sunnah of Prophet

Muhammad (pbuh) and quoting his

Hadiths, explaining the Tafseer

of the Holy Quran, the Fiqh and

other Islamic sciences of

Tradition (I'lm). He was the

seat of knowledge, the one who

extended the Chain of Golden

Narration.

Imam

Al‑Jawaad was aware of many

intellectual centers of learning

in the Islamic world in

particular in Medina and Mecca

(Hijaz), Kufa, Basrah, Qum,

Egypt, and now the biggest of

all, Baghdad, all having fast

growing devotees.

Year 212H:

Al-Jawaad's reflection about his

devotees:

Al‑Jawaad

reflected on the devotees of

Ahlul Bayt at the time. He knew

that the Shi'a (Imamah‑Asserters)

were all over the vast Muslim

Ummah, with many ministers [Naqeeb]

and representatives [Wakeel] who

collected the Zakat and Khums

funds, and distributed the funds

to the needy and indigent. His

representatives were in Egypt,

Iraq, Persia, Yemen, and Syria

forming a vast and formidable

network. He knew that even in

his absence away from Medina

these funds were distributed to

the poor and disadvantaged in

various areas, and to the Syeds

in Medina according to their

status. It was like a government

inside the Abbasi government, he

thought, but what counted most

was the application of Islam as

Islam was supposed to be

understood and applied.

Under Imam

Al-Jawaad's directions, his

representatives allowed their

partisans to work in the Abbasi

administration more than ever

before, some becoming governors,

Qadhi, or having high ranks in

the office of the Wazir. (Al-Kaafi,

Vol. V, Page 111. Also

Al-Istibsaar, Al-Toosi, Vol. II,

Page 58.)

Thankfully, Benu Abbas encouraged

Al-Jawaad to teach, give

verdicts, and answer the scholars

as much as he wanted, he was

unhampered. That was a great

opportunity, far better than the

times facing many of his

forefathers.

SEVEN YEARS LATER,

LEAVING MEDINA TO BAGHDAD:

AL‑JAWAAD GOES

BACK IN MEMORY

Year 224H:

The year was 224H, and after

having spent seven wonderful

years in Medina, now Imam

Al‑Jawaad was on his way to

Baghdad for the second time,

since he had been irrevocably

requested by Khalifa Al‑Mu'tasim

to move to Baghdad. Al‑Jawaad

had no choice but to comply.

Imam

Al‑Jawaad knew that the travel

was arduous, for they had to

cover a distance of 1,100 mile on

the backs of animals. He was in

the company of his wife Umm Al‑Fadhl

who was a niece of the present

Khalifa. By this time Al‑Jawaad

had a child by the name of

Al‑Haadi (Al-Naqi) whom he left

behind with his mother, Samaanah,

in Medina. (Al-Haadi

(Al-Naqi), born in Medina, was

cared for by his family with

utmost care and gentleness, and

he was raised under the exclusive

tutelage of his father,

Al-Jawaad.)

Al-Jawaad's works in Medina:

Thus left to

himself, Imam Al‑Jawaad reviewed

his stay in his beloved Medina.

It was seven years' stay, he

thought, full of the wonderful

teaching and engagement in

dialogues with scholars.

It was true

that the lure of Baghdad had

attracted many people, scholars

and commoners alike, but still

Medina held tremendous appeal.

The reason for that, Imam

Al‑Jawaad knew, was the existence

at that period of time of a

plethora of Hadiths

incorrectly‑quoted by its

narrators, in other words they

were in error. To directly reach

the correct source of Islamic

knowledge (I'lm) learned people

and scholars consulted mainly

Ahlul Bayt. That is why the

learned people were persistently

attracted to the Golden Chain of

Narration, concerning Sunnah,

Hadith matters, Tafseer, Halal

and Haram verdicts, Fiqh

problems, and other sciences of

Tradition.

Imam

Al‑Jawaad was glad to have

carried his responsibility. He

reviewed the numerous meetings in

his house or in the Masjid

Al‑Nabawi, whereby circles of

discussions took place daily.

Myriad of questions were directed

to him, easy or difficult, having

to do with all aspects of life,

and he was always answering to

the point, without fatigue, and

with a cheerful countenance.

►

Al‑Jawaad knew how

much people respected him and how

they looked up to him, even in an

age that glorified the elders.

One incident stood out, and that

was in regard to his father's

uncle, Ali son of Al‑Saadiq, who

was a highly respected scholar

with a large following of

students. Al‑Jawaad remembered

how one day when he came to join

the circle of discussion his

great‑uncle (Ali son of

Al‑Saadiq) stood up out of

respect, calling him the Imam,

though Al-Jawaad was much younger

than him. When his uncle's

followers (who were surprised at

the gesture) asked, Ali Ibn

Al-Saadiq replied, “He is my Imam

as Allah has ordained.” (Madinatul

Ma'aajiz, Page 450.)

Al-Jawaad's evaluation of the

schools of thought:

Al‑Jawaad's

thoughts went to the backing and

patronage of the works of Ahlul

Bayt with him as the Imam.

Al-Jawaad was so glad things had

gone smoothly in Medina during

his first absence in Baghdad

years before, and after he

returned to Medina the

administration had continued.

Al‑Jawaad was also thankful that

he had complete freedom in

preaching, teaching and

delivering the message of Islam

as Muhammad (pbuh) had taught

it. They were sweet days, very

sweet.

Imam Al‑Jawaad

knew that some devotees of

Islamic schools of thoughts were

becoming radical, meaning their

way of thinking was [in their

minds] the only right one. This

became true especially of the

Maaliki and Hanafi schools. By

now however, the beginnings then

popularity of the Shafi'i

movement, especially in Egypt was

taking place. (Al-Shafi'i

was tutored by Al-Zuhri and Ibn

U'yainah, both of whom were

students of Imam Al-Saadiq.

Al-Shafi'i also studied at the

hands of Ibn Malik. He formed a

school of thought, was popular in

Baghdad for a while. Al-Shafi'i

left for Egypt and stayed for a

short period, where he was

physically attacked by the

Maaliki followers since he

criticized some Maaliki beliefs.

Al-Shafi'i died as a result of

these injuries at the age of 54

years. The movement of

Al-Shafi'i became popular in

Egypt, then it spread in

Palestine and Syria.

(See Tawaali Al-Ta'sees,

Ibn Hajar, Page 86.)

The Mu'tazila

continued to be strong in Iraq

especially with the encouragement

of Al‑Ma'Moon. Another growing

movement whose followers were

radical was As'haab Al‑Hadith,

those who took the Hadith

literally.

Al-Jawaad and Khalifa Al-Mu'tasim:

Imam

Al‑Jawaad's thoughts took him

further, for now Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

had been dead for a good many

years, and his brother Al‑Mu'tasim

was in his place. Khalifa Al‑Mu'tasim,

Al‑Jawaad noticed, had more or

less followed the same course of

his brother Al‑Ma'Moon. Imam

Al‑Jawaad was thankful that his

activities were not hampered by

Al‑Mu'tasim, but now he was being

called to Baghdad to enlighten

the public. This was the reason

Al‑Jawaad was on his way to

Baghdad with his wife Umm Al‑Fadhl.

Al-Jawaad and his married life:

Imam Al‑Jawaad

reflected once more about his

relation with Umm Al‑Fadhl and

how un-satisfying their marriage

had been. Her personality never

seemed to agree with his, she was

so selfish, egotistic and

self‑indulgent. She repulsed

him, he knew, but it was best to

treat her as the Shari'ah had

dictated. Al‑Jawaad had married

Samaanah by whom he had a son,

[Al-Haadi], whom he loved very

much, taught him the Islamic

sciences thoroughly.

Unfortunately, Al-Jawaad had to

leave his son behind. Samaanah

was of the progeny of the great

Sahaabi Ammar Ibn

Yasir.

Imam

Al‑Jawaad knew of the tremendous

appeal of the teaching of Ahlul

Bayt and the spiritual pull it

had on people, and he wished the

very best for his son to carry on

the task. Benu Abbas were not to

be trusted; he remembered what

they had done to his forefathers

all in quest of power and for the

sake of the throne. Al‑Jawaad

hoped to serve Allah well in his

second stay in Baghdad, as much

as he disliked being there.

UPON ARRIVAL IN

BAGHDAD

The year was

about 224H and Imam Al‑Jawaad was

in his twenties when he arrived

in Baghdad. (Seerah

of the Twelve Imams, H.M. Al-Hassani,

Vol. 2, Page 436.)

He was received with great pomp,

lavish ceremony, and was welcomed

with the highest respect.

Khalifa Al‑Mu'tasim seemed to

have loved Al‑Jawaad and

appreciated him very much.

Al‑Jawaad, however, did not want

to live in the Royal Palace;

instead, he rented a house nearby

and lived in that house. He made

himself available to all people

for consultations, counsel, and

discourses. He continued to

avail himself as the seat of

learning.

Imam

Al-Jawaad also continued to

attend the meetings held at the

Khalifa Palace for giving

verdicts and solving Fiqh

problems presented. Though

Baghdad was brimming with

scholars in those years,

Al‑Jawaad was the very man

everyone seemed to need. This

led to resentments of some people

in the government who felt

challenged by the new arrival, it

was too much of a challenge for

them. This resentment grew with

time.

AL‑JAWAAD'S

PERSON:

Imam

Al‑Jawaad was the first son of

Al‑Ridha, he had distinct

qualities, high personal caliber,

and a total devotion to Islam.

Al‑Jawaad was exceptionally

brilliant and not unlike his

forefathers his manner of

deduction, explanation of Fiqh

problems, and Hadith narration

caught the attention of many

scholars early on. Al‑Jawaad's

Imamah started early and it was

the subject for investigative

evaluation by curious scholars.

They soon discovered that he was

unparalleled in his grasp or

volume of Islamic Tradition, I'lm.

That made him sought after by the

scholars and the commoners alike.

►

Appearance: Imam

Al‑Jawaad was fair in complexion,

with an appearance commanding

respect and high esteem. He

often had a smile on his face, a

radiant countenance, and a

cheerful look with repose, all of

which gave people a sense of

comfort and ease in his presence.

He put on

unpretentious clothes which later

he donated to the indigent and

poor, after using them for a

short time.

►

Similarities with

his forefathers: Imam Al‑Jawaad

showed similar personal traits to

those of his forefathers:

Imam

Al‑Jawaad loved to pray, say

Du'aas, and used to do Sujood

frequently, whenever he wanted to

thank Allah. Al‑Jawaad used to

fast often (voluntary fasting)

during the year.

Al‑Jawaad

was a very kind person, known for

his compassion, thus the

entitlement of Al‑Jawaad, meaning

the benevolent. His kindness and

character remained unchanged

throughout his lifetime. His

courtesy and affection toward

friends and distinguished

companions were well known to

all.

The needy

and indigent flocked to him,

whether he was in Baghdad or in

Medina. He was ever helpful and

generous. The poor had

allowances of charity, and

Al‑Jawaad's deputies gave fixed

allowances to the needy in

various provinces over the vast

Muslim Ummah.

►

Discourse

Capacity: People held Imam

Al‑Jawaad in high regard and were

very attracted by his

discussions. He was renowned for

answering numerous questions

about Fiqh, Al‑Ah'kaam such as

Halal and Haram, quoting the

Hadith of the Prophet (pbuh),

Tafseer, and other Islamic

sciences. It is said that one

authority alone had registered

about 30,000 Fiqh intricacies

(inquiries) which Al‑Jawaad had

answered and clarified. (Usool

Al-Kaafi, Vol. 1, Page 496. Also

Al-Manaaqib, Vol 2, Page 430.)

Al‑Jawaad

used to hold discussions in the

Masjid Al‑Nabawi, in which he

answered any question posed

whether by devotees or those

wanting to learn.

►

Personal Habits:

Al‑Jawaad cared for the feeling

of others and was most gracious

to them. He helped anyone who

was in need. The door of his

house was always open for anyone

wishing to enter for

discussions. He did not assign a

person at the door to give

preference to any person over the

other —he had no guards. All his

servants and employees were

treated equally and fairly, even

though he was the son‑in‑law of

the Khalifa (Al‑Ma'Moon).

Al‑Jawaad

was described as never to have

been crude or rough with anybody

and was exceptionally good to his

domestics and attendants.

Though

Al-Jawaad was the son‑in‑law of

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon he preferred

the minimum means of comfort at

his headquarters and home. He

refused to live in the Royal

Palace in Baghdad, instead he

preferred to live in a rented

house not too far from the

opulent Khalifa Palace, but to be

available to render counsel.

►

The Students:

Despite his young age, not only

did Imam Al‑Jawaad teach but was

always ready to counsel, give

edicts, enlighten, or quote the

Hadith. Al‑Jawaad was not

hampered in his works during his

Imamah, so he took advantage of

the freedom available to him.

The discourses were lively and

Al‑Jawaad ever vigorous, was

actively contributing, tirelessly

working, and patiently explaining

the various Islamic sciences be

they Sunnah, Tafseer, Hadith,

Fiqh or Al-Ah'kaam such as Halal

and Haram.

Al‑Jawaad

was the 9th link in the Golden

Chain of Narration.

AL‑JAWAAD'S

CHARACTER:

Imam

Al‑Jawaad was the embodiment of

high character and virtue. As

was the case with the previous

Imams, the outstanding merit (Al‑Fadhl)

and perfection of character were

gathered in him.

►

Ethics and

Character: Imam Al‑Jawaad was

the best example in his conduct

and he was the model for others

to emulate. Like his forefathers

Imam Al‑Jawaad was a very

virtuous person who emphasized

piety and was its prototype and

model.

Imam

Al‑Jawaad was endearingly

referred to as Ibn Al‑Ridha, and

he was renowned for being the

most pious of men in his time,

the most knowledgeable in

Shari'ah and Fiqh (Islamic Law),

and the most generous and the

noblest.

Al‑Jawaad

talked when need be or when the

occasion was proper, he was

silent when need be, answered

questions when directed to him.

►

Generosity: Imam

Al‑Jawaad was uncommonly

hospitable and a very generous

person, who was known for helping

others in need. The needy,

disadvantaged, and those under

financial pressure were gladly

assisted. Al‑Jawaad's generosity

was even more pronounced during

the darkness of the nights so

that no one would see him when

giving. (Al-Waafi

Bil Wafi'yyat, Vol. 4, Page 105.)

►

Al‑Ma'Moon

describes him: While still a

young man, Imam Al‑Jawaad was

requested by order of Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

to leave Medina and relocate in

Baghdad. Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon was

an astute man and a very

calculating person. He wanted to

bind himself to Imam Al‑Jawaad

through marriage, for he had

known much about Al‑Jawaad

beforehand. Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon

wanted to marry his daughter to

Al‑Jawaad. When many of Benu

Abbas disputed the Khalifa about

his intention, Al‑Ma'Moon said,

“Ahlul Bayt have been singled

out among others for the

outstanding merit which you have

seen. Even youthfulness in years

does not prevent them from

attaining perfection of

intellect.....” (It

is possible that the move was to

bring friendly relationship with

the Devotees of Ahlul Bayt, but

more likely to stunt the works of

the Institute (Al-Howza Al-Ilmiyyah)

in Medina. By taking away Al-Howza's

fountainhead (Imams), the

cohesiveness and the integrity of

the works in Medina would

decline. That was the reason

Haroon Al-Rashid imprisoned Imam

Al-Kadhim, thus take him away

from Medina, then Khalifa Al-Ma'Moon

having pressed on Imam Al-Ridha

to leave Medina and be the

heir-apparent, and now Khalifa

Al-Ma'Moon repeating the demand

on Imam Al-Jawaad but under

different pretext. (See Al-Irshad,

Al-Mufeed, page 489)

Even then,

and though Imam Al‑Jawaad married

the daughter of Al‑Ma'Moon (Umm

Fadhl), both of them teenagers,

Imam Al‑Jawaad continued

unchanged in his exceptionally

noble character —he refused to

live in the Royal Palace despite

the urging of his wife. He could

not stand the opulence of the

headquarters with its

undercurrent un‑Islamic

practices. He continued to

attend the Royal Palace to

counsel, and to resolve any

intricate Fiqh question or answer

anyone who posed an issue, yet he

refused to be a part and parcel

of the Palace's Court life.

Al-Jawaad

did not regard his marriage to

Umm Al-Fadhl (daughter of Al-Ma'Moon)

as an asset, for he had no desire

for wealth or riches. His

marriage to Umm Al-Fadhl did not

change his kindness or

benevolence, nor any of his

characteristics.

THE ISLAMIC

MOVEMENTS

The times of

Imam Al‑Jawaad were contemporary

to rich learning and fabulous

wealth, more concentrated in the

capital, Baghdad, and vicinity,

and other large towns. It was

popularly called the golden age.

It was a time of high

intellectual movements, with an

elite class of people highly

prized in the society, but with

another class of ignorant masses.

At this

period the Muslim Ummah was the

dominant power, the only

superpower of the world. The

Ummah stretched from Spain to

certain parts of India, including

all of North Africa, Syria

Proper, Iraq, Persia, Arabia,

Afghanistan, part of India, and

Central Asia (Oxus).

The wealth

and standard of living were high,

much higher than ever in the past

despite the grueling civil war

between Khalifa Al‑Amin and his

brother Al‑Ma'Moon. There was

social well‑being, vigor, and

vitality. Islam was robust and

had shaped the nation with an

entrenched Islamic culture,

despite the political situation.

During

Al‑Jawaad's Imamah some Islamic

movements became popular, with a

helping hand of the ruling class:

-

The

Hanafi

movement was becoming

increasingly popular in Iraq.

-

The

Maaliki

movement was popular in Hijaz,

Spain, and parts of North

Africa.

-

The

Shafi'i

movement was becoming

increasingly popular in Egypt

and parts of Syria.

These

nascent schools were offshoots of

the teachings of Ahlul Bayt,

since both Ibn Malik and Abu

Hanifa were active students of

Imam Al‑Saadiq. As to

Al‑Shafi'i, he was tutored by

students of Imam Al‑Saadiq

especially Al‑Zuhri and Ibn

U'yainah and also Ibn Malik.

-

The movement of

As'haab

Al‑Hadith was growing

in Baghdad.

-

The

Mu'tazila movement was

popular in Iraq, it was

endorsed and supported by

Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon then Al-Mu'tasim.

The Mu'tazila were an

off‑shoot of the Murji'ah

movement that had almost died

by now.

These

movements were heading toward

radicalization, with the

followers of each movement

insisting that their Fiqh and way

of thinking was the correct form

in absolute terms. This tendency

grew with time, and it became

dangerous later on.

►

As to Ahlul Bayt's

teachings, they remained

unchanged, were sought after

especially by the learned men and

the scholars. The

Imamah‑Asserters depended on

their own internal strength and

resolve, without support of the

ruling class and despite frequent

harassment. During Al‑Jawaad's

Imamah the teachings of Ahlul

Bayt was unhampered and continued

at a good rate.

THE UMMAH AND WEST

MEDITERRANEAN

The Ummah

was already in High Abbasi times,

but the areas remoter from the

center of the Khalifa government

were evolving a distinct

historical pattern. This was

especially true in the largest

distant region —the Muslim lands

of the western Mediterranean

basin. Most Muslim provinces of

the west Mediterranean had never

been subjected to Abbasi rule at

all. There the Berber population

were converted en masse as tribes

and assimilated to the Arabs from

the start.

►

In Spain: Under

the leadership of Musa Ibn Naseer

and Tariq Ibn Ziyad, the Berbers

had crossed into Spain in much

the same spirit as that in which

the Arabs had come into the

Fertile Crescent. In Spain the

Berbers who had come over were an

unruly governing class alongside

a still more limited number of

Arab families. When Benu Umayya

rule foundered, a young member of

the family, Abdul Rahman, escaped

the massacre of his cousins and

after numerous adventures arrived

in Spain. Abdul Rahman was able

to persuade the diverse groups

among Spain's ruling Muslims to

accept him as arbiter under the

title of

Amir [commander],

instead of a governor sent by the

upstart Abbasi. Abdul Rahman and

his successors managed to

maintain a delicate supremacy for

over a century and a half,

supported sometimes by a new bloc

of Arab families from Syria. In

the tenth century one of Abdul

Rahman's scions transformed this

Umayya emirate into an absolute

rule as a Khalifa modeled on that

of the Abbasi.

Spain's

Latinized population had been

ruled before the conquest by an

aloof Germanic aristocracy and a

rigid church hierarchy —which

combined to repress any

intellectual or civic stirrings.

Under Islam most of the cities

were readily at the disposal of

the new, more liberal, Muslim

rulers, who had allowed the

desperately persecuted Jews their

freedom and left the Christian

population to their local Roman

institutions.

Renewed

prosperity and Muslim prestige

rested largely on contacts with

the expansive economy further

east; it was from the Abbasi

domains [Baghdad] that cultural

fashions were set in Spain. But

these cultural fashions were so

much more attractive than what

the Spaniards had been used to,

that they were readily adopted by

all the population.

The leading

Christian elements in the

Muslim‑ruled area tended to share

Islamic culture, learning Arabic

more than Latin.

The area

brought under Muslim control by

the first conquests, which had

included almost all Spain and

much of southern Gaul, was

steadily eroded away during the

emirate period of Spain. The

Frankish dynasty of northern

Gaul, and most notably

Charlemagne, succeeded in driving

the Muslims out of Gaul. These

Christians in turn, under petty

kings in several little states,

advanced at the expense of the

Muslim power, whose main centers

were in the more fertile and

populous south. Before long,

Spain was divided between a

prosperous Muslim‑ruled south

[centered on Cordoba and the

Guadelquivj basin] in regular

contact with the east

Mediterranean Muslims, and a

smaller zone of Christian‑ruled

kingdoms in the north. (The

Venture of Islam, Marshall

Hodgson, Vol. 1, Pages 209-310.)

►

In Morocco:

In the far west of the Maghrib

(Morocco), another refugee from

the Abbasi rule, Idrees Ibn

Abd‑Allah, [of Imam Ali's

progeny] persuaded a number of

local tribes to accept his lead

as a descendant of Muhammad. He

himself lived only long enough

to provide a tomb which became a

shrine for all the area (Mawlai

Idrees). His son, Idrees II

however, established a dynasty

which retained the allegiance of

the area and founded the inland

city of Fas (Fez). Fas became a

center of international commerce

and Islamic culture. More

important than any political

role, the Idreesi presence became

the starting point for extensive

missionary work among the

population, especially by

immigrants (of Imam Ali's

lineage) and their progeny, who

could count on the tribesmen

respect on account of their

descent.

►

In Algeria:

In the more central and eastern

Maghrib, the Berber resistance

had accepted the leadership of

Khariji theorists. This state

proved prosperous and hospitable

to Muslim refugees from

elsewhere, notably from Abbasi

rule. Its merchants took

advantage of the trans‑Saharan

trade which was increasing along

with the Mediterranean trade in

the eastern Maghrib (now Tunisia

and Tripoli). (The Venture of

Islam, Marshall Hodgson, Vol. 1,

Page 311.)

►

In Tunisia

and Tripoli:

In the eastern Maghrib, it was

the Abbasi governors themselves

who became independent, in the

line of Ibrahim Ibn Aghlab,

[Al‑Rashid's governor]. Khalifa

Haroon Al‑Rashid had exempted the

province from control by the

central bureaucracy and required

only a lump‑sum payment from its

revenue. Under Khalifa Al‑Ma'Moon,

the

Aghaalib made their own

policies with little reference to

the Khalifa.

►

It was probably a

much growing commercial

prosperity, in which the shipping

from Muslim lands predominated

and gave Muslims an advantage,

that led the Aghaalib to occupy

Sicily and several parts of

southern Italy taking over from

the Byzantines. Sicily remained

mostly under Muslim rule for

about two centuries.

►

Despite the close

ties of the eastern Maghrib to

the east, the lands of the whole

Berber‑associated region, both

the Maghrib itself and Spain,

maintained close contact among

themselves. When the U'lamaa

subsequently crystallized their

Shari'ah, the Maghrib and Spain

were the chief areas that

accepted Maaliki school of

thought.

►

By the time of Al‑Ma'Moon,

the most active parts of the

population of most of the Khalifa

State were Muslim, and the

Khilaafah had been reaffirmed as

an absolute monarchy. No

alternative had proved viable

within the primary region of

Khalifa power, the historic lands

from Nile to Oxus.

►

Correspondingly,

the culture of that region was

coming to be carried on in

Arabic. All the major dialogues

of the high culture of the

following centuries were well

launched in their new Arabic

forms: the courtly tradition,

centered on a literary Adab and

on Hellenistic [Greek] learning,

and the Shari'ah tradition of the

Piety‑minded U'lamaa among the

bourgeois. It was within the

Islamic tradition, likewise, that

the more active forms of

religious concern and personal

piety were developing. The

social concern and factional

disputes of the Piety‑minded were

yielding to a broad range of

religious activity answering to

the broader spectrum of the

population that were now Muslims.

(The Venture of Islam, Marshall

Hodgson, Vol. 1, Page 313.)

AL‑JAWAAD DIES

Imam

Al-Jawaad was sick [said with

poison], he grew weak and the

weakness was progressive. (It

is reported that Imam Al-Jawaad's

condition was caused by poisoning

through his wife, Umm Al-Fadhl,

the daughter of Khalifa Al-Ma'Moon,

which was at the instigation of

Khalifa Al-Mu'tasim. It is also

reported by some authorities that

Al-Jawaad was in his twenties

when he died.)

Just like his grandfather

Al‑Kadhim before him, Al‑Jawaad

died in a strange land away from

his family and loved ones, many

were very upset because they

thought there was foul play. He

died in his twenties, at such a

tender age, with the potential of

tremendous productivity for Islam

if he but lived to a ripe age.

Al‑Jawaad

was buried beside the burial site

of his grandfather, Imam

Al‑Kadhim.

And You designed us

by Thy wisdom only through Thy

choice.

And You are testing

us by Thy commands and prohibitions

by way of trial.

And You supported us

by the tools of faculties.

And You provided us

with myriads of means.

And You charged us

with what we can bear.

And You have enjoined

on us to obey Thee.