THE SPREAD OF ISLAM AMONG THE CHRISTIANS OF

SPAIN (ANDALUSIA)

A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith

T.W. Arnold Ma. C.I.F

Professor Of Arabic, University Of London, University College. Written in 1896, revised in 1913

Rearranged by Dr. A.S. Hashim

|

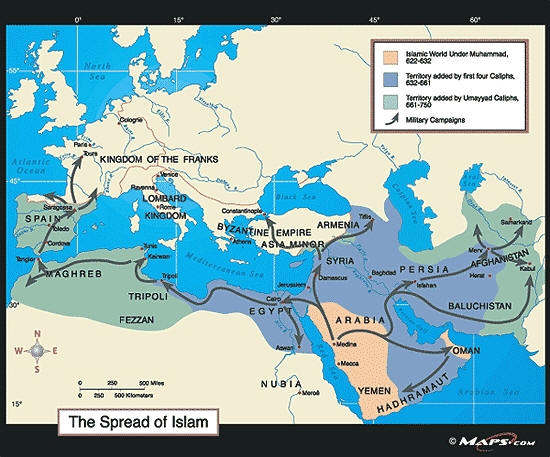

In 711 the victorious Arabs introduced Islam into Spain: in 1502 an edict of Ferdinand and Isabella forbade

the exercise of the Muslim religion throughout the kingdom.

|

|

During the centuries that elapsed between these two dates; Muslim Spain had written one of the brightest pages

in the history of medieval Europe. Her influence had passed through Provence into the other countries of Europe, bringing into birth a new poetry and a new culture, and it was

from her that Christian scholars received what of Greek philosophy and science they had to stimulate their mental activity up to the time of the Renaissance. But these triumphs

of the civilized life—art and poetry, science and philosophy—we must pass over here and fix our attention on the religious condition of Spain under the Muslim rule.

|

When the Muslims first brought their religion into Spain they found Catholic Christianity firmly established

after its conquest over Arianism.

The sixth Council of Toledo had enacted that all kings were to swear that they would not suffer the exercise

of any other religion but the Catholic, and would vigorously enforce the law against all dissentients, while a subsequent law forbade any one under pain of confiscation of his

property and perpetual imprisonment, to call in question the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church, the Evangelical Institutions, the definitions of the Fathers, the decrees of the

Church, and the Holy Sacraments.

The clergy had gained for their order a preponderating influence in the affairs of the state;

the bishops and chief ecclesiastics sat in the national councils, which met to settle the most important business of the realm, ratified the election of the king and claimed the

right to depose him if he refused to abide by their decrees.

|

The Christian clergy took advantage of their power to persecute the Jews, who formed a very large community in

Spain; edicts of a brutally severe character were passed against such as refused to be baptized;

|

|

and the Jews consequently hailed the invading Arabs as their deliverers from such cruel oppression, they garrisoned the captured cities

on behalf of the Arabs and opened the gates of towns that were being besieged.

|

|

The Muslims received as warm a welcome from the slaves, whose condition under the Gothic rule was a very

miserable one, and whose knowledge of Christianity was too superficial to have any weight when compared with the liberty and numerous advantages they gained, by throwing in

their lot with the Muslims.

|

|

These down-trodden slaves were the first converts to Islam in Spain. The remnants of the heathen population of

which we find mention as late as A.D. 693,

probably followed their example.

|

|

Many of the Christian nobles, also, whether from genuine conviction or from other motives, embraced the new creed.

|

|

Many converts were won, too, from the lower and middle classes, who may well have embraced Islam, not merely outwardly, but from genuine conviction, turning to it from a

religion whose ministers had left them ill-instructed and uncared for, and busied with worldly ambitions had plundered and oppressed their flocks.

|

|

Having once become Muslims, these Spanish converts showed themselves zealous adherents of their adopted faith,

and they and their children joined themselves to the Puritan party of the rigid Muslim theologians as against the careless and luxurious life of the Arab aristocracy.

|

At the time of the Muslim conquest

the old Gothic virtues are said by Christian

historians to have declined and given place to effeminacy and corruption, so that the Muslim rule appeared to them to be a punishment sent from God on those who had gone astray

into the paths of vice;

but such a statement is too frequent a commonplace of the ecclesiastical historian to be accepted in the absence of contemporary evidence.

|

But certainly as time went on, matters do not seem to have mended themselves;

and when Christian bishops took

part in the revels of the Muslim court,

when Episcopal sees were put up to auction and persons suspected to be atheists appointed as shepherds of the faithful,

and these in

their turn bestowed the office of the priesthood on low and unworthy persons,

we may well suppose that it was not only in the province of Elvira

that Christians turned from a religion,

the corrupt lives of whose ministers had brought it into discredit,

and sought a more congenial atmosphere for the moral and spiritual life in the pale of Islam.

|

We hear nothing of forced conversion

or anything like persecution in the early days of the Arab conquest. Indeed, it was probably in a great measure their tolerant attitude towards the Christian religion that

facilitated their rapid acquisition of the country.

The only complaint that the Christians could bring against their new rulers for treating them differently to

their non-Christian subjects, was that they had to pay the usual capitation-tax of:

|

forty-eight dirhams for the rich,

|

|

twenty-four for the middle classes, and

|

|

twelve for those who made their living by manual labor :

|

this, as being in lieu of military service, was levied only on the able-bodied males.

Women, children, monks, the halt, and the blind, and the sick, mendicants and slaves

were exempted therefrom.

This must moreover have appeared the less oppressive as being collected by the Christian officials themselves.

Except in the case of offences against the Muslim religious law, the Christians were

tried by their own judges and in accordance with their own laws.

They were left undisturbed in the exercise of their religion;

the sacrifice of the mass was offered, with the swinging of censers, the ringing of the bell, and all the other solemnities of the Catholic ritual; the psalms were chanted in

the choir, sermons preached to the people, and the festivals of the Church observed in the usual manner. And in the ninth century at least, the Christian laity wore the same

kind of costume as the Arabs.

We read also of the founding

of several fresh monasteries in addition to the numerous convents both for monks and nuns that flourished undisturbed by the Muslim rulers. The monks could appear publicly in

the woolen robes of their order and the priest had no need to conceal the mark of his sacred office,

nor at the same time did their religious profession prevent the Christians from being entrusted with high offices at court,

or serving in the Muslim armies.

Certainly those Christians who could reconcile themselves to the loss of political power had little to

complain of, and it is very noticeable that during the whole of the eighth century we hear of only one attempt at revolt on their part, namely at Beja, and in this they appear

to have followed the lead of an Arab chief.

Those who migrated into French territory in order that they might live under a Christian rule, certainly fared no better than the co-religionists they had left behind.

In 812 Charlemagne interfered to protect the exiles who had followed him on his retreat from Spain from the

exactions of the imperial officers. Three years later Louis the Pious had to issue another edict on their behalf, in spite of which they had soon again to complain against the

nobles who robbed them of the lands that had been assigned to them. But the evil was only checked for a little time to break out afresh, and all the edicts passed on their

behalf did not avail to make the lot of these unfortunate exiles more tolerable, and in the Cagots (i.e. canes Gothi), a despised and ill-treated class of later times, we

probably meet again the Spanish colony that fled away from Muslim rule to throw themselves upon the mercy of their Christian co-religionists.

The toleration of the Muslim government towards its Christian subjects in Spain

and the freedom of intercourse between the adherents of the two religions brought about a certain amount of assimilation in the two communities. Inter-marriages became frequent;

|

Isidore of Beja, who fiercely inveighs against the Muslim conquerors, records the

marriage of Abd al-Aziz, the son of Musa, with the widow of King Roderic, without a word of blame.

|

|

Many of the Christians adopted Arab names, and in outward observances imitated to some

extent their Muslim neighbors, e.g. many were circumcised,

|

|

and in matters of food and drink followed the practice of the " unbaptized pagans."

|

|

The very term Muzarabes (i.e. mustaribin or Arabicised) applied to the Spanish Christians living under Arab

rule, is significant of the tendencies that were at work.

|

|

The study of Arabic very rapidly began to displace that of Latin throughout the country,

so that the language of Christian theology came gradually to be neglected and forgotten.

|

|

Even some of the higher clergy rendered themselves ridiculous by their ignorance of

correct Latinity.

It could hardly be expected that the laity would exhibit more zeal in such a matter than the clergy,

|

and in 854 a Spanish writer brings the following complaint against his Christian fellow-countrymen :—

|

"While we are investigating the Muslim sacred ordinances and meeting together to study the sects of their

philosophers—or rather philo-braggers—not for the purpose of refuting their errors, but for the exquisite charm and for the eloquence and beauty of their language—neglecting the

reading of the Scriptures, we are but setting up as an idol the number of the beast. (Apoc. xiii. 18.)

Where nowadays can we find any learned layman who, absorbed in the study

of the Holy Scriptures, cares to look at the works of any of the Latin Fathers?

Who is there with any zeal for the writings of the Evangelists, or the Prophets, or Apostles?

Our

Christian young men, with their elegant airs and fluent speech, are showy in the Muslim dress and carriage, and are famed for the learning of the gentiles;

Intoxicated with Arab

eloquence our men greedily handle, eagerly devour and zealously discuss the books of the Muslims,

and make them known by praising them with every flourish of rhetoric, knowing

nothing of the beauty of the Churchs literature, and looking down with contempt on the streams of the Church that flow forth from Paradise;

Alas! the Christians are so ignorant

of their own law, the Latins pay so little attention to their own language, that in the whole Christian flock there is hardly one man in a thousand who can write a letter to

inquire after a friends health intelligibly, while you may find a countless rabble of all kinds of them who can learnedly roll out the grandiloquent periods of the Arab tongue.

They can even make poems, every line ending with the same letter, which display high flights of beauty and more skill in handling meter than the gentiles themselves possess."

|

In fact the knowledge of Latin so much declined in one part of Spain that it was found necessary to translate

the ancient Canons of the Spanish Church and the Bible into Arabic for the use of the Christians.

While the brilliant literature of the Arabs exercised

such a fascination and was

so zealously studied, those who desired an education in Christian literature had little more than the materials that had been employed in the training of the barbaric Goths, and

could with difficulty find teachers to induct them even into this low level of culture.

As time went on this want of Christian education increased more and more. In 1125 the

Muzarabes wrote to King Alfonso of Aragon:

|

"We and our fathers have up to this time been brought up among the Muslims, and having been baptized, freely

observe the Christian ordinances;

but we have never had it in our power to be fully instructed in our divine religion;

for, subject as we are to the infidels who have long oppressed us, we have never ventured to ask for teachers

from Rome or France;

and they have never come to us of their own accord on account of the barbarity of the

heathen whom we obey."

|

From such close intercourse with the Muslims and so diligent a study of their literature—when we find even so

bigoted an opponent of Islam as Alvar

acknowledging that the Quran was composed in such eloquent and beautiful language that even Christians could not help reading and admiring it—we should naturally expect to find

signs of a religious influence: and such indeed is the case.

Elipandus, bishop of Toledo (ob. 810), an exponent of the heresy of Adoptionism—according to which the Man

Christ Jesus was Son of God by adoption and not by nature—is expressly said to have arrived at these heretical views through his frequent and close intercourse with the Muslims.

This new doctrine appears to have spread quickly over a great part of Spain, while it was successfully propagated in Septimania, which was under French protection, by Felix,

bishop of Urgel in Catalonia.

Felix was brought before a council, presided over by Charlemagne, and made to abjure his error, but on his return to Spain he relapsed into his old heresy, doubtless (as was

suggested by Pope Leo III at the time) owing to his intercourse with the Muslims who held similar views.

When prominent churchmen were so profoundly influenced by their contact with Muslims, we may judge that the

influence of Islam upon the Christians of Spain was very considerable, indeed in A.D. 936 a council was held at Toledo to consider the best means of preventing this intercourse

from contaminating the purity of the Christian faith.

It may readily be understood how these influences of Islamic thought and practice—added to definite efforts at

conversion—would

lead to much more than a mere approximation and would very speedily swell the number of the converts to Islam so that their descendants, the so-called Muwali —a term denoting

those not of Arab blood— soon formed a large and important party in the state, indeed the majority of the population of the country,

and as early as the beginning of the ninth century we read of attempts made by them to shake off the Arab rule, and on several occasions later they come forward actively as a

national party of Spanish Muslims.

We have little or no details of the history of the conversion

of these

New-Muslims. Instances appeared to have occurred right up to the last days of Muslim rule, for when the army of Ferdinand and Isabella captured Malaga in 1487, it is recorded

that all the renegade Christians found in the city were tortured to death with sharp-pointed reeds, and in the capitulation that secured the submission of Purchena two years

later, an express promise was made that renegades would not be forced to return to Christianity.

Some few apostatized to escape the payment of some penalty inflicted by the law-courts.

|

But the majority of the converts were no doubt won over by the imposing influence of the faith of Islam

itself, presented to them as it was with all the glamour of a brilliant civilization,

having a poetry, a philosophy and an art well calculated to attract the reason and dazzle the imagination :

while in the lofty chivalry of the Arabs there was free scope for the exhibition of manly prowess and the knightly virtues—a career closed to the conquered Spaniards that

remained true to the Christian faith.

Again, the learning and literature of the Christians must have appeared very poor and meager when compared

with that of the Muslims, the study of which may well by itself have served as an incentive to the adoption of their religion.

Besides, to the devout mind Islam in Spain could offer the attractions of a pious and zealous Puritan party

with the orthodox Muslim theologians at its head, which at times had a preponderating influence in the state and struggled earnestly towards a reformation of faith and morals.

|

Taking into consideration the ardent religious feeling that animated the mass of the Spanish Muslims and the

provocation that the Christians gave to the Muslim government through their treacherous intrigues with their coreligionists over the border, the history of Spain under Muslim

rule is singularly free from persecution.

With the exception of three or four cases of genuine martyrdom, the only approach to anything like persecution during the whole period of the Arab rule is to be found in the severe

measures adopted by the Muslim government to repress the madness for voluntary martyrdom that broke out in Cordova in the ninth century.

|

At this time a fanatical party came into existence among the Christians in this part of Spain (for apparently the Christian Church in the rest

of the country had no sympathy with the movement), which set itself openly and unprovokedly to insult the religion of the Muslims and blaspheme their Prophet, with the

deliberate intention of incurring the penalty of death by such misguided assertion of their Christian bigotry.

|

|

This strange passion for self-immolation displayed itself mainly among priests, monks and nuns between the

years 850 and 860. It would seem that brooding, in the silence of their cloisters, over the decline of Christian influence and the decay of religious zeal, they went forth to

win the martyrs crown—of which the toleration of their infidel rulers was robbing them—by means of fierce attacks on Islam and its founder. Thus, for example, a certain monk, by

name Isaac, came before the Qadhi and pretended that he wished to be instructed in the faith of Islam; when the Qadhi had expounded to him the doctrines of the Prophet, he burst

out with the words: "He hath lied unto you (may the curse of God consume him!), who, full of wickedness, hath led so many men into perdition, ..... seek the eternal salvation of

the Gospel of the faith of Christ?"

|

|

On another occasion two Christians forced their way into a mosque and there reviled the Muslim religion,

which, they declared, would very speedily bring upon its followers the destruction of hell-fire.

|

Though the number of such fanatics was not considerable,

the Muslim government grew alarmed, fearing that such contempt for their authority and disregard of their laws against blasphemy, argued a widespread disaffection and a possible

general insurrection, for in fact, in 853 Muhammad I had to send an army against the Christians at Toledo, who, incited by Eulogius, the chief apologist of the martyrs, had

risen in revolt on the news of the sufferings of their co-religionists.

He is said to have ordered a general massacre of the Christians, but when it was pointed out that no men of any intelligence or rank among the Christians had taken part in such

doings

(for Alvar himself complains that the majority of the Christian priests condemned the martyrs),

the king contented himself with putting into force the existing laws against blasphemy with the utmost rigor. The moderate party in the Church seconded the efforts of the

government; the bishops anathematized the fanatics, and an ecclesiastical council that was held in 852 to discuss the matter agreed upon methods of repression

that eventually quashed the movement.

But under the Berber dynasty of the Almoravids

at the beginning of the twelfth

century, there was an outburst of fanaticism on the part of the theological zealots of Islam in which the Christians had to suffer along with the Jews and the liberal section of

the Muslim population—the philosophers, the poets and the men of letters. But such incidents are exceptions to the generally tolerant character of the Muslim rulers of Spain

towards their Christian subjects.

One of the Spanish Muslims who was driven out of his native country in the last expulsion of the Moriscoes

(Spaniards convert to Islam) in 1610, while protesting against the persecutions of the Inquisition, makes the following vindication of the toleration of his co-religionists:

|

"Did our victorious ancestors ever once attempt to extirpate Christianity out of Spain, when it was in their

power ?

Did they not suffer your forefathers to enjoy the free use of their rites at the same time that they wore

their chains?

Is not the absolute injunction of our Prophet, that whatever nation is conquered by Muslim steel, should, upon

the payment of a moderate annual tribute, be permitted to persevere in their own pristine persuasion, how absurd soever, or to embrace what other belief they themselves best

approved of ?

If there may have been some examples of forced conversions, they are so rare as scarce to deserve mentioning,

and only attempted by men who had not the fear of God, and the Prophet, before their eyes, and who, in so doing, have acted directly and diametrically contrary to the holy

precepts and ordinances of Islam which cannot, without sacrilege, be violated by any who would be held worthy of the honorable epithet of Muslims. . . .

You can never produce, among us, any bloodthirsty, formal tribunal, on account of different persuasions in

points of faith, that anywise approaches your execrable Inquisition.

Our arms, it is true, are ever open to receive all who are disposed to embrace our religion; but we are not

allowed by our sacred Quran to tyrannize over consciences.

Our proselytes have all imaginable encouragement, and have no sooner professed Gods Unity and His

Apostles mission but they become one of us, without reserve; taking to wife our daughters, and being employed in posts of trust, honor and profit; we contenting ourselves with

only obliging them to wear our habit, and to seem true believers in outward appearance, without ever offering to examine their consciences, provided they do not openly revile or

profane our religion : if they do that, we indeed punish them as they deserve; since their conversion was voluntarily, and was not by compulsion."

|

This very spirit of toleration was made one of the main articles in an account of the "Apostasies and Treasons

of the Moriscoes," drawn up by the Archbishop of Valencia in 1602 when recommending their expulsion to Philip III, as follows : " That they commended nothing so much as that

liberty of conscience, in all matters of religion, which the Turks, and all other Muslims, suffer their subjects to enjoy"

|

What deep roots Islam had struck in the hearts of the Spanish people may be

judged from the fact that when the last remnant of the Moriscoes was expelled from Spain in 1610, these unfortunate people still clung to the faith of their fathers, although

for more than a century they had been forced to outwardly conform to the Christian religion,

And in spite of the emigrations that had taken place since the fall of Granada, nearly 500,000 are said to

have been expelled at that time.

Whole towns and villages were deserted and the houses fell into ruins, there being no one to rebuild them.

These Moriscoes were probably all descendants of the original inhabitants of the country, with little or no

admixture of Arab blood; the reasons that may be adduced in support of this statement are too lengthy to be given here; one point only in the evidence may be mentioned, derived

from a letter written in 1311, in which it is stated that of the 200,000 Muslims then living in the city of Granada, not more than 500 were of Arab descent, all the rest being

descendants of converted Spaniards.

|

|

Finally, it is of interest to note that even up to the last days of its power in Spain, Islam won converts to

the faith, for the historian, when writing of events that occurred in the year 1499, seven years after the fall of Granada, draws attention to the fact that among the Moors were

a few Christians who had lately embraced the faith of the Prophet.

|

Makkarī, vol. i. pp. 280-2.

Dozy (2), tome ii. pp. 45-6.

A. Müller, vol. ii. p. 463.

Dozy (2), tome ii. pp. 44-6.

So St. Boniface (A.D. 745, Epist. lxii.).

Dozy (3), tome i. pp. 15-20. Whishaw, pp. 38, 44.

Dozy (2), tome ii. p. 210.

Bishop Egila, who was sent to Southern Spain by Pope Hadrian I, towards the end of the eighth century, on a mission to counteract the growing influence of Muslim

thought, denounces the Spanish priests who lived in concubinage with married women. (Helfferich, p. 83.)

Alvari

Cordubensis, Epist. xix. "Ob meritum æternæ retributionis devovi me sedulum in lege Domini consistere." (Migne: Patr. Lat., tom. cxxi. p. 512.)

"(Andreas

Schottus: Hispaniæ Illustratæ, tom. iv. p. 53.) (Francofurti, 1603-8.)

Dozy (2), tome ii. p. 41. Whishaw, p. 17.

Dozy (2), tome ii. p. 39.

Baudissin, pp. 11-13, I96.

Eulogius: Mem. Sanct., lib. i. § 30,

Eulogius, ob. 859 (Mem. Sanct. lib. iii. c 3) speaks of churches recently erected (ecclesias nuper structas). The chronicle falsely ascribed to Luitprand

records the erection of a church at Cordova in 895 (p. 1113).

Eulogius: Mem. Sanct., lib. iii. c. 11 (p. 812).

Id. p. 21, and John of Gorz, § 128 (p. 306).

Dozy (2), tome1 ii. p. 42.

See the letter of Pope Hadrian I to the Spanish bishops

Isidori Pacensis Chronicon, § 42 (p. 1266).

Alvar: Indic. Lum., § 35 (p. 53). John of Gorz, § 123 (p. 303).

Letter of Hadrian I, p. 385. John of Gorz, § 123 (p. 303).

Some Arabic verses of a Christian poet of the eleventh century are still extant, which exhibit considerable skill in handling the language and metre. (Von

Schack, II. 95.)

Abbot Samson gives us specimens of the bad Latin written by some of the ecclesiastics of his time, e.g. "Cum contempti essemus simplicitas christiana," but his correction

is hardly much better, " contenti essemus simplicitati christianæ " (pp. 404, 406).

Alvar: Indic. Lum., § 35 (pp. 554-6).

Von Schack, vol. ii. p. 96.

Alvar: Ind. Lum.. § 29. " Compositionem verborum, et preces omnium eius membrorum quotidie pro eo eleganti facundia, et venusto confectas eloquio,

nos hodie per eorum volumina et oculis legimus et plerumque miramur." (Migne : Patr. Lat., tome cxxi. p. 546.)

"Postmodum

transgressus legem Dei, fugiens ad paganos consentaneos, periuratus effectus est." Frobenii dissertatio de hæresi Elipandi et Felicis, § xxiv. (Migne : Patr. Lat.,

tome ci. p. 313.)

Pseudo-Luitprandi Chronicon, § 341 (p. 1115). " Basilius Toletanum concilium contrahit; quo providetur, ne Christiani detrimentum acciperent convictu Saracenorum."

There is little record of such, but they seem referred to in the following sentences of Eulogius (Liber Apologeticus Martyrum, § 20), on Muḥammad :

Dozy (2), tome ii. p. 53.

Lea, The Moriscos, pp. 17, 18.

Eulogius : Mem. Sanct. Pref., § 2. (Migne, tom. cxv. p. 737.)

The number of the martyrs is said not to have exceeded forty. (W. H. Prescott: History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, vol. i. p. 342, n.) (London 1846.)

Dozy (2), tome ii. pp. 161-2.

Eulogius : Mem. Sanct. I, iii. c. vii. (p. 805). " Pro eo quod nullus sapiens, nemo urbanus, nullusque procerum Christianorum huiusce modi rem perpetrasset, idcirco

non debere universos perimere asserebant, quos non præit personalis dux ad prælium."

Alvar: Indic. Lum., § 15.

Morgan, vol. ii. pp. 297-8, 345.

Lea, The Moriscos, p. 259.

Stirling-Maxwell, vol. i. p. 115.

|

|