THE SPREAD OF ISLAM AMONG THE CHRISTIAN

NATIONS OF AFRICA

North Africa

A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith

T.W. Arnold Ma. C.I.F

Professor Of Arabic, University Of London, University College. Written in 1896, revised in 1913

Rearranged by Dr. A.S. Hashim

|

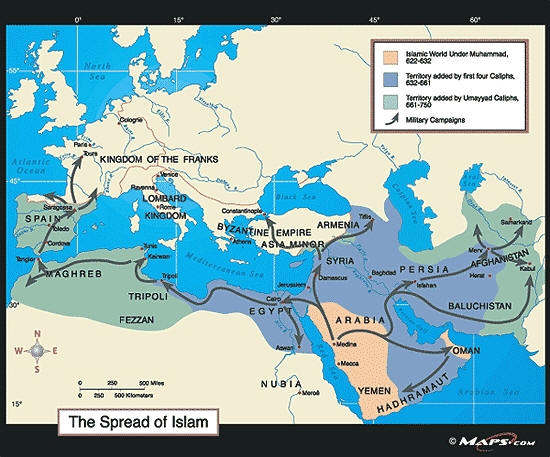

We must return now to the history of Africa in the seventh century, when the Arabs were pushing their

conquests from East to West along the north coast.

The comparatively easy conquest of Egypt, where so many of the inhabitants assisted the Arabs in bringing the

Byzantine rule to an end,

found no parallel in the bloody campaigns and the long-continued resistance that here barred their further

progress,

and half a century elapsed before the Arabs succeeded in making themselves complete masters of the north coast

from Egypt to the Atlantic Ocean.

|

It was not till 698 that the fall of Carthage brought the Roman rule in Africa to an end for ever, and the

subjugation of the Berbers made the Arabs supreme in the country.

The details of these campaigns is no part of our purpose to consider, but rather to attempt to discover in

what way Islam was spread among the Christian population.

Unfortunately the materials available for such a purpose are lamentably sparse and insufficient. What became

of that great African Church that had given such saints and theologians to Christendom? The Church of Tertullian, St. Cyprian and St. Augustine, which had emerged victorious out

of so many persecutions, and had so stoutly championed the cause of Christian orthodoxy, seems to have faded away like a mist.

In the absence of definite information, it has been usual to ascribe the disappearance of the Christian

population to fanatical persecutions and forced conversions on the part of the Muslim conquerors. But there are many considerations that militate against such a rough and ready

settlement of this question.

-

First of all, there is the absence of definite evidence in support of such an assertion.

-

Massacres, devastation and all the other accompaniments of a bloody and long-protracted war, there were in

horrible abundance, but of actual religious persecution we have little mention,

-

and the survival of the native Christian Church for more than eight centuries after the Arab conquest is a

testimony to the toleration that alone could have rendered such a survival possible.

|

The causes that brought about the decay of Christianity in North Africa must be sought for elsewhere than in

the bigotry of Muslim rulers.

But before attempting to enumerate these, it will be well to realize how very small must have been the number

of the Christian population at the end of the seventh century—

a circumstance that renders its continued existence under Muslim rule still more significant of the absence of

forced conversion, and leaves such a hypothesis much less plausibility than would have been the case had the Arabs found a large and flourishing Christian Church there when they

commenced their conquest of northern Africa.

|

The Roman provinces of Africa, to which the Christian population

was confined, never extended far southwards;

the Sahara forms a barrier in this direction, so that the breadth of the coast seldom exceeds 80 or 100 miles.

Though there were as many as 500 bishoprics just before the Vandal conquest, this number can serve as no criterion of the number of the faithful, owing to the practice observed

in the African Church of appointing bishops to the most inconsiderable towns and very frequently to the most obscure villages,

and it is doubtful whether Christianity ever spread far inland among the Berber tribes.

When the power of the Roman Empire declined in the fifth century, different tribes of this great race, known to the Romans under the names of Moors, Numidians, Libyans, etc.,

swarmed up from the south to ravage and destroy the wealthy cities of the coast. These invaders were certainly heathen.

The Libyans, whose devastations are so pathetically

bewailed by Synesius of Cyrene, pillaged and burnt the churches and carried off the sacred vessels for their own idolatrous rites,

and this province of Cyrenaica never recovered from their devastations, and Christianity was probably almost extinct here at the time of the Muslim invasion.

The Moorish

chieftain in the district of Tripolis, who was at war with the Vandal king Thorismund (496-524), but respected the churches and clergy of the orthodox, who had been ill-treated

by the Vandals, declared his heathenism when he said, " I do not know who the God of the Christians is, but if he is so powerful as he is represented, he will take vengeance on

those who insult him, and succor those who do him honor."

There is some probability that the nomads of Mauritania also were very

largely heathen.

|

But whatever may have been the extent of the Christian Church, it received a blow from the Vandal persecutions

from which it never recovered. For nearly a century the Arian Vandals persecuted the orthodox with relentless fury; sent their bishops into exile, forbade the public exercise of

their religion and cruelly tortured those who refused to conform to the religion of their conquerors.

|

|

When in 534, Belisarius crushed the power of the Vandals and restored North Africa to the Roman Empire, only 217 bishops met in the Synod of Carthage

to resume the direction of the Christian Church. After the fierce and long-continued persecution to which they had been subjected the number of the faithful must have been very

much reduced, and during the century that elapsed before the coming of the Muslims,

|

|

the inroads of the barbarian Moors, who shut the Romans up in the cities and other centers of

population, and kept the mountains, the desert and the open country for themselves,

the prevalent disorder and ill-government, and above all the desolating plagues that signalized the latter half of the sixth century, all combined to carry on the work of

destruction.

|

|

Five millions of Africans are said to have been consumed by the wars and government of the Emperor Justinian. The wealthier citizens abandoned a country whose

commerce and agriculture, once so flourishing, had been irretrievably ruined. Such was the desolation of Africa, that in many parts a stranger might wander whole days without

meeting the face either of a friend or an enemy.

|

|

The nation of the Vandals had disappeared; they once amounted to an hundred and sixty thousand warriors, without including the

children, the women, or the slaves. Their numbers were infinitely surpassed by the number of Moorish families extirpated in a relentless war; the same destruction was retaliated

on the Romans and their allies, who perished by the climate, their mutual quarrels, and the rage of the barbarians."

|

From the considerations enumerated above, it may certainly be inferred that the Christian population at the

time of the Muslim invasion was by no means a large one. During the fifty years that elapsed before the Arabs assured their victory, the Christian population was still further

reduced by the devastations of this long conflict. The city of Tripolis, after sustaining a siege of six months, was sacked, and

of the inhabitants part were put to the sword and the rest carried off captive into Egypt and Arabia.

In fact, many of the great Roman cities were quite depopulated, and remained uninhabited for a long time or were even left to fall to ruins entirely,

while in several cases the conquerors chose entirely new sites for their chief towns.

As to the scattered remnants of the once flourishing Christian Church that still remained in Africa at the end

of the seventh century, it can hardly be supposed that persecution is responsible for their final disappearance, in the face of the fact that traces of a native Christian

community were to be found even so late as the sixteenth century. Idris, the founder of the dynasty in Morocco that bore his name, is indeed said to have compelled by force

Christians and Jews to embrace Islam in the year A.D. 789, when he had just begun to carve out a kingdom for himself with the sword,

but, as far as I have been able to discover, this incident is without parallel in the history of the native Church of North Africa.

The very slowness of its decay is a testimony to the toleration it must have received. About 300 years after

the Muslim conquest there were still nearly forty bishoprics left,

and when in 1053 Pope Leo IX laments that only five bishops could be found to represent the once flourishing African Church,

the cause is most probably to be sought for in the terrible bloodshed and destruction wrought by the Arab hordes that had poured into the country a few years before and filled

it with incessant conflict and anarchy.

In the course of the next two centuries, the Christian Church declined still further, and in 1246 the bishop of Morocco was the sole spiritual leader of the remnant of the

native Church.

Up to the same period traces of the survival of Christianity were still to be found among the Kabils of Algeria;

these tribes had received some slight instruction in the tenets of Islam at an early period, but the new faith had taken very little hold upon them, and as years went by they

lost even what little knowledge they had at first possessed, so much so that they even forgot the Muslim formula of prayer.

Shut up in their mountain fastnesses and jealous of

their independence, they successfully resisted the introduction of the Arab element into their midst, and thus the difficulties in the way of their conversion were very

considerable.

Some unsuccessful attempts to start a mission among them had been made by the inmates of a monastery belonging to the Qadiriyyah order, Saqiyah al-hamra, but the

honor of winning an entrance among them for the Muslim faith was reserved for a number of Andalusian Moors who were driven out of Spain after the taking of Granada in 1492.

They

had taken refuge in this monastery and were recognized by the sheikh to be eminently fitted for the arduous task that had previously so completely baffled the efforts of his

disciples. Before dismissing them on this pious errand, he thus addressed them :

|

"It is a duty incumbent upon us to bear the torch of Islam into these regions that have

lost their inheritance in the blessings of religion;

for these unhappy Kabils are wholly unprovided with schools, and have no sheikh to teach

their children the laws of morality and the virtues of Islam; so they live like the brute beasts, without God or religion.

To do away with this unhappy state of things, I have determined to appeal to your

religious zeal and enlightenment.

Let not these mountaineers wallow any longer in their pitiable ignorance of the grand

truths of our religion; go and breathe upon the dying fire of their faith and re-illumine its smoldering embers; purge them of whatever errors may still cling to them from their

former belief in Christianity; make them understand that in the religion of our Prophet Muhammad— may God have compassion upon him—dirt is not, (as in the Christian religion),

looked upon as acceptable in the eyes of God.

I will not disguise from you the fact that your task is beset with difficulties, but

your irresistible zeal and the ardor of your faith will enable you, by the grace of God, to overcome all obstacles.

Go, my children, and bring back again to God and His Prophet these unhappy people who

are wallowing in the mire of ignorance and unbelief.

Go, my children, bearing the message of salvation, and may God be with you and uphold

you."

|

|

The missionaries started off in parties of five or six at a time in various directions; they went in rags,

staff in hand, and choosing out the wildest and least frequented parts of the mountains, established hermitages in caves and clefts of the rocks.

|

|

Their austerities and prolonged

devotions soon excited the curiosity of the Kabils, who after a short time began to enter into friendly relations with them.

|

|

Little by little the missionaries gained the

influence they desired through their knowledge of medicine, of the mechanical arts, and other advantages of civilization, and each hermitage became a center of Muslim teaching.

|

|

Students, attracted by the learning of the new-comers, gathered round them and in time became missionaries of Islam to their fellow-countrymen, until their faith spread

throughout all the country of the Kabils and the villages of the Algerian Sahara.

|

|

The above incident is no doubt illustrative of the manner in which Islam was introduced among such other

sections of the independent tribes of the interior as had received any Christian teaching, but whose knowledge of this faith had dwindled down to the observance of a few

superstitious rites;

for, cut off as they were from the rest of the Christian world and unprovided with spiritual teachers, they could have had little in the way of positive religious belief to

oppose to the teachings of the Muslim missionaries.

|

|

There is little more to add to these sparse records of the decay of the North African Church.

|

|

A Muslim

traveler,

who visited al-Jarid, the southern district of Tunis, in the early part of the fourteenth century, tells us that the Christian churches, although in ruins, were still standing

in his day, not having been destroyed by the Arab conquerors, who had contented themselves with building a mosque in front of each of these churches.

|

|

Ibn Khaldun (writing

towards the close of the fourteenth century), speaks of some villages in the province of Qastiliyyah,

with a Christian population whose ancestors had lived there since the time of the Arab conquest.

|

|

At the end of the following century there was still to be found in the city of Tunis a small community of native Christians, living together in one of the suburbs, quite

distinct from that in which the foreign Christian merchants resided; far from being oppressed or persecuted, they were employed as the bodyguard of the Sultan.

These were doubtless the same persons as were congratulated on their perseverance in the Christian faith by Charles V after the capture of Tunis in 1535.

|

This is the last we hear of the native Christian Church in North Africa. The very fact of its so long survival

would militate against any supposition of forced conversion, even if we had not abundant evidence of the tolerant spirit of the Arab rulers of the various North African

kingdoms, who employed Christian soldiers,

granted by frequent treaties the free exercise of their religion to Christian merchants and settlers,

and to whom Popes

recommended the care of the native Christian population, while exhorting the latter to serve their Muslim rulers faithfully.

Littmann, pp. 68-70. K. Cederquist: Islam and Christianity in Abyssinia, p. 154 (The Moslem World, vol. ii.).

C. O. Castiglioni: Recherches sur les Berbères atlantiques, pp. 96-7 (Milan, 1826.)

Synesii Catastasis. (Migne: Patr. Gr., tom. lxvi. p. 1569.)

Gibbon, vol. iv. pp. 331-3.

Tijānī, p. 201. Gibbon, vol. v. p. 122.

Neander (1), vol. v. pp. 254-5. J. E. T. Wiltsch: Hand-book of the geography and statistics of the Church, vol. i. pp. 433-4. (London, 1859.) J. Bournichon:

L'lnvasion musulmane en Afrique, pp. 32-3. (Tours, 1890.)

[95] Leo Africanus. (Ramusio, torn. i. p.

70, D.)

"Deusen, una città antichissima edificata da Romani dove confina il regno di Buggia col diserto di Numidia." (Id. p. 75, F.)

"Tous

ceux qui ne se convertirent pas à I'islamisme, ou qui (conservant leur foi) ne voulurent pas s'obliger à payer la capitation, durent prendre la

fuite devant les armées musulmanes.” (Tijānī, p. 201.)

Leo Africanus. (Ramusio, tom. i. p. 7.)

"Afros

passim ad ecclesiasticos ordines (procedentes) prætendentes nulla ratione suscipiat (Bonifacius), quia aliqui eorum Manichæi, aliqui rebaptizati sæpius sunt probati."

Epist. Iv. (Migne: Patr, Lat., tom. lxxxix, p. 502.)

Leo Africanus. (Ramusio, pp. 65, 66, 68, 69, 76.)

Qayrwān or Cairoan, founded A.H. 50; Fez, founded A.H. 185; al-Mahdiyyah, founded A.H. 303; Masīlah, founded A.H. 315; Marocco, founded A.H. 424. (Abū-l Fidā, tome

ii. pp. 198, 186, 200, 191, 187.)

A doubtful case of forced conversion is attributed to Abd al-Mu'min, who conquered Tunis in 1159.

De Mas Latrie (2), pp. 27-8.

S. Leonis IX. Papæ Epist. lxxxiii. (Migne: Patr. Lat., tom. cxliii. p. 728.) This letter deals with a quarrel for precedence between the bishops of Gummi and

Carthage, and it is quite possible that the disordered condition of Africa at the time may have kept the African bishops ignorant of the condition of other sees besides

their own and those immediately adjacent, and that accordingly the information supplied to the Pope represented the number of the bishops as being smaller than it really

was.

A. Müller, vol. ii. pp. 628-9.

S. Gregorii VII. Epistola xix. (Liber tertius). (Migne: Patr. Lat., tom. cxlviii. p. 449.)

De Mas Latrie, p. 226. A number of Spanish Christians, whose ancestors had been deported to Morocco in 1122, were to be found there as late as 1386, when they were

allowed to return to Seville through the good offices of the then sultan of Morocco. (Whishaw, pp. 31-4.)

C. Trumelet: Les Saintes de 1'Islam, p. xxxiii. (Paris, 1881.)

Compare the articles published by a Junta held at Madrid in 1566. for the reformation of the Moriscoes; one of which runs as follows : " That neither themselves,

their women, nor any other persons should be permitted to wash or bathe themselves either at home or elsewhere; and that all their bathing houses should be pulled down and

demolished." (J. Morgan, vol. ii. p. 256.)

C. Trumelet: Les Saints de 1'Islam, pp. xxviii-xxxvi.

Leo Africanus says that at the end of the fifteenth century all the mountaineers of Algeria and of Buggia, though Muhammadans, painted black crosses on their

cheeks and palms of the hand (Ramusio, i. p. 61); similarly the Banū Mzab to the present day still keep up some religious observances corresponding to excommunication and

confession (Oppel, p. 299), and some nomad tribes of the Sahara observe the practice of a kind of baptism and use the cross as a decoration for their stuffs and weapons.

(De Mas Latrie (2), p. 8.)

The modern Touzer, in Tunis.

Ta'rīkh al-duwal al-islāmiyyah bi'l maghrib, I. p. 146. (ed. De Slane. Alger, 1847.)

Leo Africanus. (Ramusio, tom. i. p. 67.)

De Mas Latrie (2), pp. 61-2, 266-7. L. del Marmol-Caravajal: De 1'Afrique, tome ii. p. 54. (Paris, 1667.)

De Mas Latrie (2), p. 192.

e.g. Innocent III, Gregory VII, Gregory IX and Innocent IV.

De Mas Latrie (2), p. 273.

Back to Book List Back to Book List

|

|